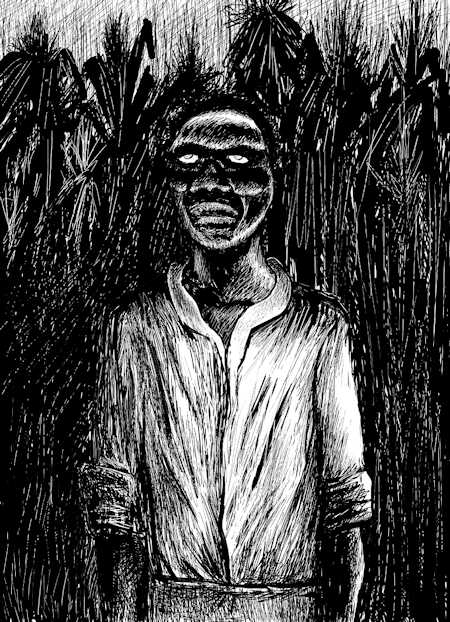

Zombie, at twilight, in a field of cane sugar of haïti. Image Souirce

James Theodore Holly, a Black American who was the first Episcopal bishop of Haiti, once called that Caribbean island nation: "the Mary Magdalene of the nations, possessed by seven devils."1 Among the devils that Holly enumerated was voodoo, a syncretistic religion practiced by about seventy percent of the Haitians. Holly's negative evaluation of voodoo's contribution to Haiti reiterates that of several other writers. Unfortunately, a good deal of what has been written on Haiti voodoo has been written "with more imagination than insight"2 according to Harmon Johnson, WorldTeam missionary to Haiti.

In the Western world, voodoo has amassed quite an exotic reputation. A core part of this African/New World hybrid religion is the worshiper's possession by the voodoo gods, the loa. This particular religious experience -- which is the focus of this essay -- has been interpreted in all kinds of ways. On the one side is William Sargant, a physician in psychological medicine. He contended that voodoo and its attendant phenomenon of loa possession is something that helps Haitians "to live lives of comparative happiness because they have found a religion that does bring their gods to them. And their gods live in them, and they live in their gods."3 On the opposite end of the spectrum are those like Bishop Holly, who considered loa possession to be demonic or satanic in origin. For Holly and others, these are real demonic encounters.

In this essay, I want to examine the possibility of a link or at least similarity between loa possession in Haiti today and the demonic possession described in Scripture. The study will be broken into two major parts. First, we'll take a look at demon possession in the Bible. An attempt will be made to establish some identifying characteristics from the various scriptural accounts. Secondly, the identifying characteristics of Haitian voodoo loa possession will be listed together with parallels that may occur in the biblical incidents of demon possession. This essay will concern itself only with demon possession and will not include cases that might be classified as the result of demonic influence.

It is beyond the scope of this essay to deal with issues of the authenticity or accuracy of the biblical accounts. For the purposes of this paper, two things will be assumed:

It will also be assumed that the demon possession in the New Testament is of supernatural origin and cannot be explained merely on the basis of present-day psychological research. If the parallels seem clear enough between biblical demon possession and Haitian loa possession, it shall be assumed that it, too, has something of the supernatural in it.

In the sources consulted for this study, different spellings are used for the name of the religion (e.g., voodoo and vodun), the names of gods or spirits (e.g., loa and loua), and for other features of this Haitian folk religion. To facilitate comprehension, the spelling of words will be consistent throughout this essay, even in quotations where the original author used a different spelling.

Haitian Vodou, often referred to as Haitian Voodoo, is a syncretic religion that originated in the Caribbean nation of Haiti. Its roots can be traced back to the merging of African religious beliefs brought to Haiti by enslaved West Africans during the transatlantic slave trade and elements of Catholicism introduced by French colonizers.

When Africans were forcibly brought to Haiti as slaves, they brought with them diverse spiritual and religious practices from various regions of Africa, including regions that are now part of present-day Benin, Nigeria, Togo, Ghana, and the Congo. These traditions included beliefs in spirits, ancestor worship, ritualistic practices, and herbal medicine.

In Haiti, these African religious beliefs and practices underwent a process of syncretism, blending with Catholicism, which was the religion of the French colonizers. This blending was a means of preserving their African spiritual heritage while outwardly conforming to the religion imposed upon them by their oppressors.

Over time, Haitian Vodou developed into a distinct religious tradition with its own rituals, deities (known as lwa or loa), ceremonies, music, dance, and iconography. It became an important aspect of Haitian culture and identity, influencing various aspects of life, including art, music, folklore, and social structures. Today, Vodou remains an central part of Haitian society.

1J. Carleton Hayden, "James Theodore Holly (1829-1911) First Afro-American Episcopal Bishop: His Legacy to Us Today," Journal of Religious Thought 33 (Spring-Summer, 1976): 53

2Harmon A. Johnson, "The Growing Church in Haiti" (Coral Gables: The West Indies Mission, 1970. Mimeographed), p. vii.

3William Sargant, The Mind Possessed: A Physiology of Possession, Mysticism, and Faith Healing (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1974), p. 181.

Within Scripture, actual possession by demons or demonic forces is almost exclusively a New Testament phenomenon. Certainly, references to demons do occur in the Old Testament. Demons or evil spirits are mentioned in such passages as Leviticus 17:7, Deuteronomy 32:17, 2 Chronicles 11:15, Psalms 95:5 and 106:37, and Isaiah 13:21 and 34:14. None of these biblical passages speak, however, of that "use of a living body by another spirit" as one writer has defined possession.4 Though spiritism is forbidden in Scripture, what is referred to in Leviticus 19, Deuteronomy 18, and Isaiah 8 does not include possession.

J. S. Wright is one of the few Old Testament scholars to assert that the Old Testament does actually contain identifiable references to demon possession. He says:

In the Bible, the pagan prophets probably sought possession. The prophets of Baal in 1 Kings 18 would come in this category. Mediums, who were banned in Israel, must have deliberately cultivated possession since the Law regards them as guilty people, not as sick (e.g. Leviticus 20:6, 27). In the Old Testament, Saul could be used as an outstanding example of unsought possession (1 Samuel 16:14; 19:9)5.

In this case that involves Saul, Wright stands almost alone in labeling it as "an outstanding example" of possession. Among other Biblical scholars, only a few, such as early Methodist scholar Adam Clarke6 and David Erdman7, allow for the possibility of actual demon possession having occurred in Saul's case. Although the scripture says that "an evil spirit from the Lord tormented (Saul)", most writers view Saul's problem as one of simple insanity. They would opt for a blanket statement like that of Laird Harris, professor at Covenant Theological Seminary: "Demon possession is not mentioned in the Old Testament."8

The picture changes considerably when we turn to the New Testament. In the New Testament, demons (daimon in Greek) are referred to more than 100 times, with many of those references involving possession. This is particularly true of the gospel accounts where J. Ramsey Michaels, professor at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, asserts: "Nothing is more certain about the ministry of Jesus than the fact that He performed exorcisms."9

Dealing with demon possession was a part of Jesus' daily life and ministry. It was also something in which He involved the Apostles and His other followers. As Bible scholar and Christian apologist Merrill Unger reminds his readers: "Not only did Jesus cast out demons, . . . but he delegated this power to the Twelve, to the Seventy, and even to believers."10

Unfortunately, only a few of the cases in Scripture are treated with sufficient detail to be of any help in this study. Even those descriptions are often briefer than one would wish. In several passages where demon possession is mentioned, it is only in passing, such as in Mark 1:32: "They brought to him all who were sick or possessed with demons." The lack of further detail doesn't provide much help for a study of this type except to support a distinction in scripture between demon possession and illness. Nine cases in the New Testament are described with enough detail to make possible some comparisons between them and modern-day phenomena such as Haitian loa possession.

The synoptic gospel authors include seven cases of demon possession for which some descriptive details are given. These are:

No case of demon possession is recorded in John's Gospel, either with or without detail. Jesus himself is, however, accused by his enemies of being demon-possessed in an episode in John 7:20-21.

The Book of Acts has two cases of demon possession described in some detail. These are:

The rest of the New Testament writings do not describe any cases of demon possession. However, demons and demonic powers are mentioned in passages like Timothy 4:1; Ephesians 6:12; James 2:19; and Revelation 9:20 and 16:14.

William W. Orr suggests that there is a clear reason for the abundance of cases of demon possession in the first part of the New Testament after almost no mention in the Old Testament and then their sudden disappearance from the Scriptures. Orr, who uses a dispensational lens to look at scripture, says it was part of the devil's strategy "to assemble the whole host of demons from all corners of the universe to thwart and defeat, if possible, the purpose of Christ's coming into the world."11

When the demons failed in that, Orr says they dispersed throughout the universe again, and this concentrated activity recorded in the New Testament subsided.

4Kyle Kristos, Voodoo (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1976),p. 12

5New Bible Dictionary, 2nd ed., s.v. "DemonPossession" by J.S. Wright.

6Adam Clarke, A Commentary and Critical Notes, Vol. 1 (Nashville: Abingdon, n.d.), p. 259.

7David Erdman, "The Books of Samuel," A Commentary on the Holy Scriptures, Vol. 5, Philip Schaff, tr. (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1877), p. 222

8Laird Harris, "One View of Demon Possession," His, March, 1975,p. 9

9J. Ramsey Michaels, "Jesus and the Unclean Spirits," in Demon Possession: A Medical, Historical, Anthropological and Theological Symposium, ed. John Warwick Montgomery (Minneapolis: Bethany Fellowship, 1976), p. 41.

10Merrill F. Unger, Biblical Demonology (Wheaton: Van Kampen Press, 1952), p. 78.

11 William W. Orr, Are Demons for Real?(Wheaton: Scripture Press Publications, 1970), p. 16.

None of the cases of demon possession identified as such and described in the Bible are exactly like the others in their manifestations. Some are certainly more sensational than others. It is possible, however, to list certain features or characteristics that seem part of demon possession. Such marks of demon possession would include:

Before leaving this data to turn to loa possession in Haiti today, one must consider the hermeneutical question: How are these descriptions to be considered? Virkler answers that question:

"We have no guarantee that the relatively brief descriptions of demonically-caused symptomatology found in Scriptures were meant to be considered normative examples of possession across time and cultures. All that the narrative accounts of demonization found in the Gospels and Acts claim is that they are accurate descriptions of demonization of that time, not normative descriptions of demonization that can be used for all succeeding generations.20"

With that caution in mind, let's now turn to the literature available on Haitian voodoo to see if parallels can be found between loa possession and the biblical accounts of demon possession.

12 Shelby Vernon McCasland, By the Finger of God: Demon Possession and Exorcism in Early Christianity in the Light of Modern Views of Mental Illness (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1951), p. 15.

13 John Livingston Nevius, Demon Possession (Fleming H. Revell, 1894; reprint ed., Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 1968), p. 288.

14 Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology edited by Leslie Shepherd. s.v. "Possession"

15 William Alexander, Demonic Possession in the New Testament (1902; reprint ed., Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1980), p. 150.

16 Graham, Dow, "The Case for the Existence of Demons," Churchman (94), p. 200. 17Unger, p. 94.

18 Ibid., p. 95.

19Ibid., p. 101.

20Henry A. and Mary B. Virkler, "Demonic Involvement in Human Life and Illness," Journal of Psychology and Theology 5 (Spring, 1977), p. 100.

An American military attaché and his wife, who spent several years in Haiti, have written: "Haiti is a magic island, and the laughter of a thousand African gods echoes through her mornes."21 These gods and their periodic possession of voodoo worshipers have fascinated anthropologists and tourists alike since the last century. Actually, voodoo should properly be defined as an ancestral worship cult. However, spirit or loa possession does play a very important part in voodoo. And this possession experience is, says Haitian psychiatrist Emerson Douyon, one of the things that Haitian society "valorizes."22 The experience is not just for the voodoo priest (a male houngan or a female mambo) or to a bokor (a shaman or sorcerer loosely linked to voodoo practice), but it is for all adherents.

Various explanations have been advanced for this phenomenon called loa possession. It has been regarded variously as a form of neurosis, as the fulfillment of a "need for self-transcendence, an attention-getter, an opportunity to act out fantasies, a chance to shed responsibility. . . mass hysteria, or masochism."23 Kristos writes of hallucination or mass hypnosis as possible explanations and then says it could be "the visitation of a supernatural being."24

Therefore, it is doubly important for any Christian working in Haiti to understand loa possession. First, loa possession is something that Haitian society values. Second, one has to decide, however tentative it may be, what these gods are whose laughter reverberates through the mountain valleys of that Caribbean island nation.

Dow argues that "there is correspondence between descriptions of present-day demonic phenomena . . . and the descriptions . . . in the New Testament."25 Anthropologist Alan Tippett goes a step further, particularizing the parallel when he says: "Probably there is no better extant example of possession phenomena in the whole world than the form known as voodoo, especially the variety in Haiti."26

What are some of the similarities or parallelisms that would lead scholars to compare what the Bible describes as demon possession with modern-day possession phenomena?

When a Haitian loa possesses a person, a markedly different personality seems to take control. "The possessed person behaves quite rationally," says Sargant, "but in the way the loa would behave."27 There are literally hundreds of loa, each with its own special voice, manners, facial expressions, and physical attributes. Each loa even has its own "food and drink preferences, color and clothing preferences" to the extent that a possessed person may even change clothes after being possessed to conform more closely to the particular loa.28

When a loa possesses a Haitian, other people in the immediate vicinity have no doubts as to the identity of the particular loa that has appeared. Later -- hours or even occasionally days -- when a possessed person returns to his normal personality, he or she will remember nothing of what transpired during the possession state. It is as though the person has truly been absent from his or her body while another being was using it.

While the Haitians do fear zombies and other kinds of spirit world creatures who appear from time to time, the loa apparently have no corporeal existence apart from the persons they possess. While paintings of Catholic saints are sometimes used in voodoo sanctuaries to represent some of the more well-known loa, these loa only appear when they have a human body to use.

While possessed, many of the Haitians exhibit mediumistic abilities. Anthropologists have documented cases of possessed persons knowing secrets to which, in normal life, they would not have had access. Haitian ethnologist Jean Price-Mars tells of possessed persons giving predictions and prophecies about the future.29

There are also some instances in which the loa acknowledge the higher authority of Jesus Christ, even as happened in New Testament times. Even given the peaceful co-existence that seems to exist between Roman Catholicism and voodoo, anthropologist Francis Huxley relates isolated instances in which loa prohibit people from going to Christian church services and forbid them to "hear the words of the Gospel."30

With Protestantism, of course, the antagonism is more pronounced. Nazarene missionary Paul Orjala tells of loa who "speak directly to the Christian through the person possessed and argue their right to do their work." 31 Haitian anthropologist Jacque Romain notes if a person becomes a born-again believer, there is an irreconcilable conflict between that person and his patron loa.

The powers that the loa or spirits give to their "horses" were explained to Oberlin College professor George Simpson by at least one voodoo priest as due to the fact that "the loa are fallen angels."33 That, of course, is the same explanation that many conservative biblical scholars give for demons.

The ability of possessed persons to physically do things not ordinarily possible for them seems even more prevalent in Haitian loa possession than it was in the cases of demon possession recorded in the Bible. Jeremie Breda mentions "an old man (who) climbs a tree like a monkey" while possessed and "a girl (who) handles a red hot iron without feeling pain."34 Anthropologist Melville Herskovits writes of the extraordinary bodily strength he had witnessed in possessed persons.35 Harold Courlander, anthropologist and folklorist, joins other writers in recounting stories of loa who cause their "horses" to eat glass or broken razor blades without causing any injuries and of other Haitians who plunge their arms into boiling oil while possessed without suffering any after effects.36

It is this characteristic of unusual physical ability that calls into serious question the explanation of loa possession as mere role enactment. Some characteristics of loa possession could be easily simulated if role-playing was all that was involved. However, the super-normal strength and abilities like those described in anthropological studies would seem difficult, if not impossible, to simulate in a merely theatrical performance.

Simpson has noted that in normal, everyday life, there is "considerable sexual modesty among the peasants."37 The picture changes radically during possession experiences. Huxley writes of the "sexual megalomania" that present in many possessions.38 Possessed persons often have to be restrained from taking off their clothes to go naked. Courlander writes of the contempt for proprieties and of the lascivious and lurid behavior and speech of some loa.39 Behavior that would be quite unacceptable to the community and even to the possessed person himself is excused because the loa -- not the person being possessed -- is responsible for unacceptable behavior and speech.

Almost without exception, the beginnings of a loa possession are marked by "trembling, by a kind of frenzy without controls or direction. (The person being possessed) may stagger, fall, and go into convulsions."40 This seizure gradually wears off, and the personality of the individual loa begins to appear. Finally, the person seems normal, except that he or she has completely switched personalities, including perhaps sex.

Sometimes possessed persons also exhibit self-destructive tendencies. "loa will cause their 'horses' to rub hot pepper into their eyes. Still others will compel possessed persons to cut themselves with machetes."41 At times, possessed persons must be restrained from throwing themselves into deep water.

loa possessions in Haiti are almost always episodic, with many of them coming during religious ceremonies (even those in the Roman Catholic church!). Physical illnesses do not accompany this type of possession. However, Frederick Conway of San Diego State University says, "When they are angry, the loa are believed to express their displeasure most frequently by making a family member ill." 42 Gerald Murray, a University of Florida professor, notes that Haitians believe that causing illness is a principal activity of the loa. The peasants do, however, differentiate between "spirit-caused illness (maladi loa) as opposed to naturally caused illness,"43 a distinction also made in the New Testament.

Loa possession occurs most often among the rural subsistence farming population and its members who may have emigrated into the cities. As in Biblical Palestine, the incidence of possession in Haiti is lower in the cities, particularly among the well-educated population. The Haitian elite have even made some unsuccessful attempts to stamp out voodoo and, for a long time, refused to grant it the status of a folk religion.

While not actively sought after, loa possession is welcomed by Haitians. This is not true in most of the possession cases in the New Testament. There do not, however, seem to be attempts on the part of the Haitians to work themselves into a state of possession. Occasionally, a tourist or even an anthropologist who has gone to watch a voodoo ceremony will be possessed without his or her having willed the possession. Huxley relates the story of a young Haitian Protestant who had gone to witness a voodoo ceremony "and despite all he could do, had been possessed."44 Sometimes, during a certain period, a voodoo worshiper may not wish to be possessed. The worshiper may even take certain countermeasures against being possessed. These precautions are not always successful, and the worshiper will sometimes be possessed against his or her will.

Upon conversion, Protestant Christians normally are freed from further loa possession experiences. Along this line, Tippett says that "the type of Protestantism most successful in Haiti is the form most hostile to voodoo because it comes into encounter with it on a meaningful level."45 The freedom born-again believers have from possession is known in Haitian society. Former missionary Orjala noted that Nazarene pastors in Haiti are continually called upon to cast out loa.46 This deliverance, when it occurs, seems to be instantaneous, even as were the deliverances recounted in New Testament documents.

On the other hand, the Roman Catholics, lacking an emphasis on a life-changing born-again experience, have been fighting a losing battle with syncretism. Today, most voodoo worshipers also consider themselves to be Roman Catholic.

When a voodoo worshiper dies, a type of transference ceremony is held in which a voodoo priest removes the "talent" of the one that had been possessed and transfers it to someone else.47

Some aspects or features of Haitian loa possession are absent from the accounts of demon possession recorded in Scripture. These include:

21 Robert Debs Heinl Jr. and Nancy Gordon Heinl, Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People 1492-1971 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1978), p. 690.

22 Emerson Douyon, "A Research Model on Trance and Possession States in Haitian Vodun," in The Haitian Potential: Research and Resources of Haiti, ed. Vera Rubin and Richard P. Schaedel (New York: Teachers College Press, 1975), p. 172.

23Heinl, p. 682.

24 Kyle Kristos, Voodoo (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1976), p. 34.

25 Dow, p. 199.

26 Writing in Demon Possession: A Medical, Historical, Anthropological, and Theological Symposium, ed. John Warwick Montgomery (Minneapolis: Bethany Fellowship, 1976), p. 155.

27 Sargant, p. 174.

28 Gerald F. Murray, "Population Pressure, Land Tenure, and Voodoo: The Economics of Haitian Peasant Ritual" in Beyond the Myths of Culture: Essays in Cultural Materialism, ed. Eric B. Ross (New York: Academic Press, 1980), p. 298.

29 Jean Price-Mars, Ainsi Parla L'oncle . . . Essais d'Ethno-graphie (Port-au-Prince, 1928; reprint ed. Ottawa: Editions Lemeac, 1972), p. 182.

30 Francis Huxley, The Invisibles (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1966), p. 113.

31 Paul Orjala, This Is Haiti (Kansas City: Nazarene Publishing House, 1961), p. 51.

32 Jacque B. Romain, Quelques Moeurs et Coutumes

des Paysans Haitiens (Port-au-Prince: L'imprimerie de 1'etat, 1959), p. 206.

33 George Eaton Simpson, "The Belief System of Haitian Vodun, American Anthropologist 47 (January, 1945), p. 46.

34 Jeremie Breda, "Life in Haiti: Voodoo and the Church," Commonweal 24 May 1963, p. 241.

35 Melville J. Herskovits, Life in a Haitian Valley (1937; reprint ed., New York: Octagon Books, 1964), p. 372.

36 Harold Courlander, The Drum and the Hoe (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1960), p. 40.

37 George Eaton Simpson, "Sexual and Familial Institutions in Northern Haiti," American Anthropologist 44 (1942), p. 669.

38 Huxley, p. 125.

39 Courlander, p. 56.

40 Ibid., p. 11

41 Ibid., p. 40.

42 Frederick J. Conway, "Pentecostalism in Haiti: Healing and Hierarchy" in Perspectives on Pentecostalism: Case Studies from the Caribbean and Latin America, ed. S.D. Glazier (Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 1980), p. 8.

43 Murray, p. 302.

44 Huxley, p. 162.

45 Tippett, p. 156.

46 Orjala, p. 51.

47 Simpson, "Belief System," p. 47.

48 Thomas E. Weil, et. al. Area Handbook for Haiti (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1973), p. 52.

49 Price-Mars, p. 193.

50 "Development Assistance Program, Agency for International Development," USAID Haiti: Department of State. Manuscript, June, 1977, p. 125.

The question now is: How should we interpret the data from the Bible and from anthropologists and missionaries? There are many similarities between biblical demon possession and loa possession in today's Haiti. Are the parallels strong enough to conclude that this is the same phenomenon?

From a biblical point of view, Joe Schubert says no: "The solution which is most consistent with the total biblical teaching is that demon possession, though a first-century reality, is not present in the twentieth century." 51 On the other end of the spectrum, Tippett says that all the characteristics of possession in Haitian voodoo "line up with the New Testament experience."52

In this search for a conclusive answer, one encounters a caution by Henry Virkler, professor of psychology at Palm Beach Atlantic University. In an article in the Journal of Psychology and Theology, Virkler says: "Nearly every symptom thought to be an indicator of demon possession is also found in the psychopathology of nondemonic origin."53

Approaching it from a non-dogmatic phenomenological angle, Graham Dow says: "A coherent understanding of certain behavioral phenomena is given by the demonic model . . . There is sufficient correspondence between the demonic model of perception and the data of human behavior."54

Granted, there are some differences between the cases of biblical demon possession and the descriptions of Haitian loa possession. However, there are enough similarities that it may easily be concluded that loa possession is demonic, following the model of the New Testament cases. Haitian believers and missionaries working in that country often identify it as demon possession. This identification has allowed them to address loa possession in a biblical manner. The weight of the evidence does tip the scales in favor of viewing loa possession as a present-day equivalent of biblical demon possession.

51 Joe Schubert, et. al. The Devil You Say? Perspectives on Demons and the Occult (Austin, Texas: Sweet Publishing Company, 1974), p. 22.

52Tippett, p. 164.

53Virkler, p. 99.

54Dow, p. 207.

Bibliography of sources used by Howard Culbertson to research Haitian voodoo loa possession and what is described as demon possession in the Bible. Please note that some of the works are by Haitian anthropologists.

Alexander, William. Demonic Possession in the New Testament. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1902; reprint ed., Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1980.

Breda, Jeremie, "Life in Haiti: Voodoo and the Church," Commonweal 24 May 1963, pp. 241-244.

Clarke, Adam. A Commentary and Critical Notes, Vol. 1. London: Butterworth, 1851; reprint ed., Nashville: Abingdon, 1977.

Conway, Frederick J. "Pentecostalism in Haiti: Healing and Hierarchy" in Perspectives on Pentecostalism: Case Studies from the Caribbean and Latin America, ed. S.D. Glazier. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 1980. Pages 7-26.

Courlander, Harold. The Drum and the Hoe: Life and Lore of the Haitian People. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1960.

"Development Assistance Program, Agency for International Development," Department of State: USAID Haiti, June, 1977. Typewritten.

Dow, Graham. "The Case for the Existence of Demons," Churchman 94: pp. 199-209.

Douyon, Emerson. "A Research Model on Trance and Possession States in Haitian Vodun," in The Haitian Potential: Research and Resources of Haiti, eds. Vera Rubin and Richard P. Schaedel. New York: Teachers' College Press, 1975. Pages 167-172.

Erdman, David. "The Books of Samuel," in A Commentary on the Holy Scriptures, Vol. 5., ed. John Peter Lange; trans., Philip Schaff. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1877.

Harris, Laird. "One View of Demon Possession," His, March, 1975, pp. 9-10.

Hayden, J. Carleton, "James Theodore Holly (1829-1911) First Afro-American Episcopal Bishop: His Legacy to Us Today," Journal of Religious Thought 33 (Spring-Summer, 1976), pages 50-62.

Heinl, Robert Debs Jr. and Nancy Gordon Heinl. Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People 1492-1971. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1978.

Herskovits, Melville Jean. Life in a Haitian Valley. 1937; reprint ed., New York: Octagon Books, 1964.

Hitt, Russell T. "Demons Today," in Demons, the Bible and You. Newton, PA.: Timothy Books, 1974.

Huxley, Francis. The Invisibles. London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1966.

Johnson, Harmon A. The Growing Church in Haiti. Coral Gables, FL: The West Indies Mission, 1970. Mimeographed.

Koch, Kurt E. Demonology, Past and Present. Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 1973.

Kristos, Kyle. Voodoo. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1976.

McCasland, Shelby V. By the Finger of God: Demon Possession and Exorcism in Early Christianity in the Light of Modern Views of Mental Illness. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1951.

Mizrach, Steve. "Neurophysiological and Psychological Approaches to Spirit Possession in Haiti."

Metraux, Alfred. Voodoo in Haiti, trans. Hugo Charteris. New York: Oxford University Press, 1959.

Montgomery, John Warwick, ed. Demon Possession: A Medical, Historical Anthropological and Theological Symposium. Minneapolis: Bethany Fellowship, 1976.

Murray, Gerald F. "Population Pressure, Land Tenure, and Voodoo: the Economics of Haitian Peasant Ritual" in Beyond the Myths of Culture: Essays in Cultural Materialism, ed. Eric B. Ross. New York: Academic Press, 1980. Pages 295-321.

New Bible Dictionary, 2nd ed., s.v. "Demon" by L.L. Morris.

New Bible Dictionary, 2nd ed., s.v. "Demon Possession" by J.S. Wright.

Nevius, John L. Demon Possession. Fleming H. Revell, 1894; reprint ed., Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 1968.

Orjala, Paul. This Is Haiti. Kansas City: Nazarene Publishing House, 1961.

Orjala, Paul Haiti Diary, comp. Kathleen Spell. Kansas City: Beacon Hill Press, 1953.

Orr, William W. Are Demons for Real? Wheaton: Scripture Press Publications, 1970.

Oesterreich, T. K. Possession: Demoniacal and Other Among Primitive Races, in Antiquity, the Middle Ages, and Modern Times. New Hyde Park, NY: University Books, 1966.

Price-Mars, Jean. Ainsi Parla L'oncle . . .Essais d'Ethnographie. Port-au-Prince, 1928; reprint ed., Ottawa: Editions Lemeac, 1972.

Romain, Jacque B. Quelques Moeurs et Coutumes des Paysans Haitiens. Port-au-Prince: L'imprimerie de 1'etat, 1959.

Sargant, William. The Mind Possessed: A Physiology of Possession, Mysticism, and Faith Healing. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1974.

Schubert, Joe, et. al. The Devil You Say? Perspectives on Demons and the Occult. Austin, Texas: Sweet Publishing Company, 1974.

Shepherd, Leslie ed. Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1978.

Simpson, George Eaton. "Sexual and Familial Institutions in Northern Haiti," American Anthropologist. 44 (1942); 655-674.

Simpson, George Eaton. "The Belief System of Haitian Vodun," American Anthropologist 47 (January, 1945): 35-59.

Simpson, George Eaton. "The Vodun Service in Northern Haiti," American Anthropologist 42 (April, 1940): 236-254.

Stewart, James S. "On a Neglected Emphasis in New Testament Theology," Scottish Journal of Theology 4 (September, 1951): 292-301.

Thoby-Marcelin, Philippe and Pierre Marcelin. The Beast of the Haitian Hills, trans. Peter C. Rhodes. New York: Time, Inc., 1964.

Unger, Merrill Frederick. Biblical Demonology: A Study of the Spiritual Forces Behind the Present World Unrest. Wheaton: Van Kampen Press, 1952.

Virkler, Henry A. and Mary B. "Demonic Involvement in Human Life and Illness," Journal of Psychology and Theology 5 (Spring, 1977): 95-102.

Weil, Thomas E., et al. Area Handbook for Haiti. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1973.

-- Howard Culbertson, hculbert@snu.edu