More classic art masterpieces used as illustrations

TL;DR:

The story of Jonah is less about a big fish and more about God's love for all people, including those we might despise. Jonah resisted God's call to preach to Nineveh because of his deep prejudice against the Ninevites. Though Jonah eventually obeyed outwardly, his heart never aligned with God’s.

"This familiar biblical story is often misinterpreted as centering around the character of Jonah. A point that has been clear to me in recent months is that the Grand Narrative has one main character with many supporting actors. In the account of Jonah, the story is about God revealing his heart for unreached people groups." -- Mendy H., Nazarene Bible College student

" 'Get up and go to the great city of Nineveh.' . . . But Jonah got up and went in the opposite direction to get away from the Lord." -- Jonah 1:2-3

What do believers generally think we should learn from Jonah's story? The takeaway I hear mentioned most often is: "Obey God."

I've heard missions mobilizer (and Nazarene MK) John Zumwalt graphically describe that particular viewpoint. Most people, John says, think the principal lesson from Jonah's story is: "Obey God, or you'll wind up as whale vomit!"

To be sure, Jonah's story supports the thought that God expects us to obey Him, but is obedience really the story's main point? I do not think so since Jonah eventually did what God asked. Jonah did go to Nineveh and preached all throughout the city. If obedience is the central issue, shouldn't everything have been hunky-dory between Jonah and God?

Well, it wasn't. Indeed, God expresses displeasure as the curtain comes down on Jonah's story. God's final words to Jonah are a question: "Should I not have compassion on Nineveh?" (Jonah 4:11, NASB)

Jonah avoided going to Nineveh because he detested the Ninevites. They were Israel's enemies, and Jonah did not share God's concern for them. Indeed, Jonah got mad when the city repented en masse, and it was not destroyed. That reaction greatly bothered God.

We'll only truly understand Jonah's story if we listen carefully to its final two verses. The main point of Jonah's story is that God loves all people groups, even -- to Jonah's dismay -- the Ninevites. That's a major reason scholars have often called Jonah "the missionary book of the Old Testament."

God clearly wants our hearts in tune with His heart on this issue. World Vision founder Bob Pierce often said, "Let my heart be broken with the things that break the heart of God." In Jonah's story, God's heart is broken when an entire society or people group is separated from Him. Jonah should not be our model. Shouldn't our hearts be burdened by the thousands of people groups still unreached with the Gospel?

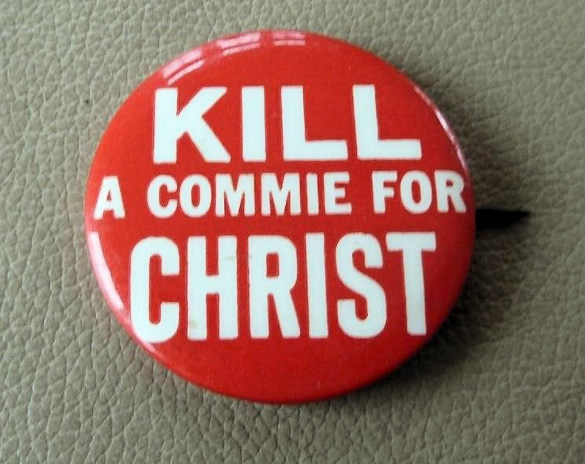

Sadly, believers today often think that whenever they feel threatened by someone, that person should not make it into the Kingdom. They rejoice when their enemies face suffering and even extermination. A few decades ago, many American Christians were vociferous about their hatred for Russians. Jonah-like slogans such as "Kill a Commie for Christ" were bandied about. After 9/11, many American Christians began seeing Muslims as the enemy. In Croatia, I discovered the people in neighboring Serbia were seen as the enemy. In many places, immigrant populations are considered the enemy.

Let's reflect carefully on the ramifications of Jonah's story. God was unhappy when Jonah did not care about a city full of people estranged from Him. Surely, God is not pleased today when His people feel little or no burden to reach the as-yet-unreached peoples of the world.

-- Howard Culbertson, hculbert@snu.edu

This blog on a world missions Bible passage is one of more than three dozen articles in the "Heart of God" series published in Engage, a monthly online magazine. That series examines what the Bible says about missions.

J -- Journeying by sea, Jonah fled in fear,

O -- Obedient to God, though reluctant at first,

N -- Not knowing the storm would come to make him hear,

A -- After three days in a fish, he prayed and reversed,

H -- Heeded God's call, bringing Nineveh to repent.

Like acrostics? Here are more of them

More on Jonah: The disease of prejudice

"The sign of Jonah . . . . God's extravagant concern for both the evil and the complacent, for Ninevites as well as Jonahs, for prostitutes as well as Pharisees, for my enemy as well as for me. . . . The puzzle of Jonah -- its perpetual source of wonder and doubt -- is this: Why is God so deeply concerned about not just Nineveh but about this man, Jonah?" -- Mark Buchanan in "Running With Jonah," Christianity Today, November 15, 1999

This essay is about the theology of world missions efforts. Its basis is an Old Testament character named Jonah, a man whose story is often used to teach obedience. The ten sections of the essay reflect on what Jonah's story says about God's desire for the entire world to be evangelized.

Lori sat in my office, tears welling up in her eyes. Her voice broke as she spoke. She had just returned to school after the Christmas break. During that time, she had attended one of the huge Urbana missionary conventions sponsored by InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. Alongside 15,000 other university students, Lori had joined some Christian university professors, missionaries, and pastors in focusing on the completion of world evangelism.

At Urbana, Lori heard a speaker say that each day, 55,000 people die before they've even heard of Jesus Christ. When she returned to school, she was still stunned by that news.

"I'll never be the same again," she said there in my office.

I know some people would think Lori was a young and impressionable young woman who was teetering on the edge of fanaticism. However, we cannot dispute that a third or more of the world's population knows nothing about Jesus Christ. Still, many think Lori was overreacting. While they wish some way could be found to get the Gospel to these unreached peoples, they do not feel an inner compulsion to do it. They excuse their lack of passion and motivation by saying that these people have their own religion. Lori need not be alarmed, they argue. They feel that everyone everywhere is talking to and trying to serve what will turn out to be the same God.

"Doesn't God accept all people's worship?" they ask. "He is merciful and understanding. So, isn't He going to save those who are sincere in following their own religion?"

The events of Jonah's story answer these questions. That's because the Ninevites were not Jews. They lived 500 miles from Jonah's Galilee home. Nineveh -- whose ruins can be seen today in modern-day Iraq -- was the capital city of the feared Assyrian empire. God's dealings with this pagan city and its inhabitants help us answer the question: Are people of other religions really lost? Answers to an oft-asked question

Note: The word "heathen" in the title is not used in a pejorative or negative sense. This was the classic way questions about the eternal destiny of the unreached or unevangelized were worded.

| "I remember when the Veggie Tales version of Jonah's story

hit the big screen. The critic for the Chicago Tribune gave it two and a half stars.

The reason being 'It didn't have much of an ending. The main character never understood

the message of the story.' "I remember sitting on a commuter train laughing my head off. I guess he's right: Jonah only deserved two and a half stars." -- Bob C., Nazarene Bible College student |

It's clear that, in God's eyes, the Ninevites were lost. That wasn't because they lacked a religion. Archaeologists digging in the ruins of ancient Nineveh have uncovered pagan temple ruins. There, they found Assyrian inscriptions with long lists of deities.

In spite of their religiosity, the people of Nineveh fell under God's judgment and were about to be destroyed. Those Ninevites -- all of them -- were tragically lost. Being sincere believers in something spiritual was not enough.

Think about it: Those under condemnation included Nineveh's religious leaders. They were not in touch with God. He could not use them to communicate His truth. The Ninevites needed an outsider to bring them God's message. in this way, they resemble those three billion people who know little or nothing of Jesus. These three billion unreached people are from about 5,000 tribes and people groups scattered mostly across Asia and into North Africa. Without cross-cultural missionary activity aimed at them, they will remain unreached because they have no Christian neighbors sharing their culture and speaking their native language. Even the most aggressive neighborhood evangelistic efforts by existing local churches will never reach these groups of people. Like the Ninevites of Jonah's time, today's unreached people will hear the gospel only if cross-cultural evangelists or missionaries go to them. Are these unreached really lost without the gospel? Jonah's story suggests that they are. [ more on the unreached ]

As a side note, we should note that Christians who say it doesn't really matter what you believe as long as you are sincere are loudly applauded by some non-believers. Some secular anthropologists denounce Christian missionaries, insisting that we leave tribal peoples alone. These anthropologists are relativists who see all religions as curious belief systems, none of which is better than any other. To them, missionaries are imperialistic intruders who trample on and even destroy tribal cultures. This does not square at all with what is really happening. Christianity has turned out to be very cross-cultural, able to be contextualized in every cultural environment. Indeed, the gospel has been a stabilizing force for many cultures. By contrast, Christians from cultures dominated by religions such as voodoo testify that such religions degrade and enslave people rather than uplifting and freeing them.

Apart from that argument, however, no human culture is static and unchanging. Our world has become one huge global village. There's little chance for any society in our world today to live in total isolation. Even if they did, the culture of that society would not be frozen and unchanging. It would be in change. The issue for even seemingly inaccessible tribal groups is not change versus no change. Instead, the question is: What kinds of change? To the chagrin of anthropologists, research shows that they and those following in their wake have tended to be more disruptive to tribal cultures than missionaries have been.

The plight of the Phoenician sailors on board the ship carrying Jonah points to the powerlessness of false gods. Those sailors prayed fervently to what they thought were real gods. Despite those prayers, the stormy winds blew more fiercely than ever.

The deities they trusted turned out to be as deaf, dumb, and powerless as the god that Elijah mocked on Mt. Carmel (1 Kings 18). In that story, the Lord God sent fire to consume an animal sacrifice on a stone altar. The pagan god Baal had been given a chance to do that first. No matter how fervently his worshipers prayed, the fire never came from him. The same God who sent the fire to Elijah's altar now stilled the raging storm around Jonah's boat. Clearly, the gods of the sailors and the God that Jonah served were not all the same being who was just being called by different names. Baal and the sailors' other deities were false gods.

Jehovah God does not, of course, calm every storm. The Apostle Paul had to swim ashore on Malta when a storm wrecked his ship. Still, one clear message of Jonah's storm experience is that which God you serve is important. That's clear in the results of the prayers of the sailors. A little later, inside that fish, Jonah lamented the fate of idol worshipers. "Those who cling to worthless idols forfeit the grace that could be theirs," he said (Jonah 2:8, NIV). By saying "worthless idols," Jonah rules out a relativism that views all religions as having the same value.

The Ninevites were likely sincere in their worship of Ishtar and other gods. Such sincerity had not, however, solved their sin problem. Their religion had not reconciled them with their Creator. Divine grace, says Jonah, is forfeited unless people forsake their idols.

Recently, someone told me he felt that Islam and Christianity are simply two ways people approach the same God. Since the followers of both religions believe in only one God, this person concluded that either religion will lead you to eternal life. The trouble with that argument is that the Muslim holy book and the Christian Bible are very contradictory. They say very different things. For instance, the Muslim holy book, the Qur'an, emphatically denies that Jesus was God incarnate whose crucifixion on a Roman cross paid the penalty for humanity's sins. The Bible says that was exactly what happened. Both books cannot be right. If one is right, the other has to be wrong.

I served as a missionary in Haiti for four years. I saw that to the average Haitian, the Christian gospel comes as very good news. The people of that Caribbean island nation are very religious. Three-fourths of them are voodoo worshipers. They fear the loa or spirits who inhabit trees and crossroads and frequently even possess people. Voodoo religious ritual aims at appeasing or even keeping away those spirits. The Haitian voodoo worshiper lives in uncertainty -- even fear -- in his or her relationship with the supernatural. Even fervent voodoo worshipers have not found real, lasting peace. To them, the gospel is liberating good news. To those Haitians I know, Christian conversion does not mean simply improving your understanding of God. To those former voodoo worshipers, Christian conversion meant moving from lostness to salvation as it did for the Ninevites.

Eighteenth-century French writer Jean Jacques Rousseau referred to tribal peoples as untainted "noble savages." He believed that human beings are intrinsically good. People's vileness, Rousseau said, comes from the corrupting effects of modern civilization. That's not true, of course. The heathen of every age and culture have been as spiritually lost as those in Nineveh. "There is no one righteous, not even one" (Romans 3:10).

Right belief is important. Still, just believing that Yahweh or Jehovah -- revealed as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit -- is the one true God, Creator of the universe, won't save anyone. At the same time, Jonah's story makes clear that what damns people is not their belief in the wrong thing. People are lost because of their sinfulness. While Jonah condemned the Ninevites' idolatry in his prayer inside the fish, it was not their idol worship alone that brought on God's judgment. Knowing the Ninevites' wickedness is key to understanding their alienation from God. That sin was an offensive stench to God. They were not saved by being zealous in their own religion. They were saved only because of their radical repentance and turning to Jehovah.

Two days after Lori Smith shared with me her burden for unevangelized peoples, I told her story to some other students. I had hoped that they would share her concern for those with little or no access to the Gospel. Many did not.

"After all, if people have love in their hearts, won't they be OK in God's sight?" one student asked. What the student was thinking was that people's good qualities can outweigh their bad ones. While that may sound reasonable, that's not the picture that the Bible reveals to us. What it says is that judgment has already befallen us. We human beings do not need a fair trial. We need forgiveness. That's clear in the first three chapters of Genesis, where the question of why we human beings are lost is answered. Without meaning to, that student was making it more -- not less -- difficult for people to get into the Kingdom. The only way we can truly love is when "the love of God is shed abroad in our hearts" (Romans 5:5). By making entrance to God's Kingdom dependent on our own merits, that student was making it impossible for those people ever to approach God.

When Adam and Eve disobeyed God, they sensed immediately that their sin had disrupted fellowship with their Creator (Genesis 3). They were right. Beginning with the story of their Fall, the Bible piles up example after example of how sin creates rifts between human beings and God.

Jonah knew that. He sensed that his disobedience had separated him from God. "I have been banished from your sight," he cries. (Jonah 2:4). Even the Ninevites must have already sensed their sinfulness. When they heard Jonah's message, they did not offer excuses. They did not argue with God over how good they had been trying to be. They acknowledged their guilt and the rightness of the punishment decreed for them (Jonah 3:10.)

Looking back over our 15 years as cross-cultural missionaries, I can think of only one person I heard say: "Well, even before I first heard the gospel, I was in a right relationship with God." Instead, the common lament was, "I was lost."

Even people with some understanding of the Gospel often rationalize away their lostness. Many nominal Roman Catholics that I met in Italy felt that at the Final Judgment God would take a look at a comparison of their good and bad deeds. That's a common belief of nominal Christians. Unfortunately for them, counterbalancing evil deeds with good ones is not the way God measures the holiness necessary to get into heaven (Hebrews 12:13). We cannot change the rules and try to dictate the terms on which we will be saved. Just because someone refuses to admit his sinful plight does not mean it's not true. Actually, since God has already done His part to reconcile us with Him, nothing is open for negotiation. The first three chapters of Paul's letter to the Romans clearly explain the whole world's sinful predicament.

The idol worshipers sailing that ship carrying Jonah sensed that someone's sin had caused the storm. Those sailors of long ago did not see every storm as a sign of divine wrath. Still, they had correctly diagnosed the cause of this one. However, as they were to find out, it wasn't their sin behind that storm. The offending sinner was their Jewish passenger, Jonah.

As Jonah's story ends, God reminds Jonah of the Ninevites' moral blindness. Some Bible commentators think Jonah 4:11 refers to lots of young children in Nineveh. In their minds the phrase "they didn't know their right hand from their left" means babies. I don't think "children" is the best interpretation of that phrase. I prefer the way Ken Taylor has paraphrased it. With all their religiosity, the Ninevites had been, writes Taylor in his Living Bible, in "utter spiritual darkness." As Jesus would later say, the Ninevites were wandering like "sheep without a shepherd." In the context of the whole story, that is the best interpretation of Jonah 4:11.

I've had students in missions classes raise the question of the fate of people in unreached peoplegroups. There are about 5,000 tribes or ethnic groups with little or no access to the gospel. They have no viable church sharing the gospel in their midst. What about those people who've never had a chance to hear about the birth, death, and resurrection of Jesus? Are they lost? How do we answer that oft-asked question?

As Abraham pleaded with God for mercy for Sodom and Gomorrah, he asked: "Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?" (Genesis 18:25). The answer is, of course, "yes." God will do right in all situations, including the cases of those who've never heard the full Gospel story. Still, God's love is seeking to draw all human beings to Him. That love shows itself in God's prevenient grace, as John Wesley and others have called it. Divine grace that seeks all lost people, offering at least a glimmer of hope. This does not mean that the heathen are not really lost. They are. "All have sinned," Scripture declares (Romans 3:23).

Some years ago, Canadian Don Richardson went as a missionary to an island that is now part of Indonesia. He spent time learning the language and culture of an unreached tribe, but then months of fruitless effort made him think about giving up. Finally, during peace-making ceremonies between two warring tribes, Richardson saw a clear illustration of what God did for us through Jesus Christ. In a book about his experience, Richardson wrote that missionaries are tempted to use prepackaged gospel messages tied to their home cultures. Instead, he says, they should be searching their target cultures for gospel illustrations. He argues that there are things in every culture that open people's eyes to the gospel.

Richardson developed this subject further in his later book, Eternity in Their Hearts. However, Richardson doesn't use that title to say all people are already reconciled with God. He's reaffirming what the Apostle Paul said about God trying to reach all people (Romans 1:19).

God has ways of making His grace known in all cultures. It appears that the heathen could respond in a way that would allow them to be reconciled with God. In the end, all people facing the Final Judgment will be "without excuse" (Romans 1:20). They have not been arbitrarily or unfairly sentenced.

Are the heathen really lost? Jonah was convinced they were, even though he wanted to walk away, leaving them that way! Unfortunately, Jonah has had a lot of company in his complacency. Unwilling to see beyond their own world, they dismiss responsibility for anybody beyond their immediate neighborhood.

As his ship headed across the Mediterranean into that storm, Jonah disappeared below deck. Instead of being conscience-stricken over his cowardly actions or agonizing over the perishing Ninevites, Jonah went to sleep. Was he lulled to sleep by relief at having escaped God's call? Or was he simply exhausted? We do know that the Ninevites' lostness did not greatly burden Jonah. It was that attitude, and not Jonah's outward disobedience, that most upset God.

Too many churches are asleep, just as Jonah was in the storm. This was brought home to me not long ago. In 1990 the communist government of the former Soviet Union crumbled. We at SNU had the opportunity to send an evangelistic team of students to Russia. Those students raised much of the money needed for that trip from family and friends. Sadly, one team member's local church said they couldn't help her to be on that short-term mission trip. The reason? They were raising money to beautify their church building. They needed to pay for new carpeting. What a bunch of Jonahs!

Fortunately, not every church has succumbed to the grip of a Jonah mentality. The Church of the Nazarene in Roswell, New Mexico, did not. That congregation had outgrown its old building. It needed land to build a larger one. Although they began accumulating money in a building fund, they couldn't find affordable property. Then, someone at a local church board meeting suggested that they "tithe" their building fund money. Instead of letting that building fund money sit unused month after month, they proposed taking some of it to help on a church building in another country. That's what they did. Then, after building one church on a mission field, they built a second one. Then, some doors began to open for their local building project. Still, they decided to keep helping others. By the time they completed their own new building, those Roswell Nazarenes had helped build five church buildings in other countries. There may have been some Jonahs in that Roswell congregation, but they were not being listened to. I fervently hope hundreds of other church boards will catch the vision for global evangelism that drove that one church.

It may not happen, however. I sometimes hear pastors or church board members grumbling at the idea of giving ten percent of their church income to evangelism ministries in other countries. "After all," these modern-day Jonahs moan, "our local church has so many expenses, and we have to support the district organization too. How can we drain off money for work in another country when that money is needed to keep our local ministry afloat?"

Like Jonah, they're sitting in the shade. Or else they're headed for Tarshish, trying to remain oblivious to the Ninevites tumbling off into eternity. Such people may believe that the heathen are lost. Still, they shrug off any responsibility to reach them, saying that a merciful God will somehow take care of the unreached. What started as an understandable reluctance to make needed sacrifices has quickly soured into carnal reasoning.

Remember my preacher friend and his sermon about the size of whale stomachs? Instead of worrying about peripheral details, that preacher should have been crying and weeping over the three billion people beyond the reach of near-neighbor evangelism efforts. He should have been pleading with his congregation to do something about those peoples untouched by the Gospel. What wasted effort he put out, squandering his Sunday morning sermon time talking about the size of whale stomachs!

Sometimes people excuse their lukewarmness toward world evangelism efforts by saying: "Well, don't Christian TV and radio cover the globe? Surely, everyone can hear the gospel that way."

Doesn't that sound like an excuse Jonah would use?

Jonah's attitude surfaced about two hundred years ago in a ministers' meeting in Nottingham, England. There, a bi-vocational pastor named William Carey was invited to suggest a discussion subject for the group of ministers.

Carey had been reading James Cook's Voyages Around the World, a travelogue book recounting British explorer James Cook's global travels. As Carey read that book, he became burdened by the spiritual condition of those peoples Cook had visited. So, that day in the late 1700s, Carey suggested that the ministers talk about "the duty of Christians to attempt the spread of the gospel among heathen nations."

Carey was stunned when the meeting leader stopped him. In an agitated voice, the moderator said: "Young man, sit down. When God pleases to convert the heathen, He will do it without your aid or mine."

Doesn't that sound like Jonah? Can't you hear that recalcitrant prophet saying: "Lord, you want a message preached in Nineveh? Then, do it yourself."

Fortunately, William Carey did not listen to that church leader. Some friends helped him start the English Baptist Missionary Society, and under its auspices in 1793, he sailed for India.

Up until that time, the 200-year-old Protestant movement had not engaged in much cross-cultural missionary outreach. Carey's efforts awakened Protestantism to its missionary responsibilities to such a degree that he is now called the "Father of Modern Missions." Jonah would not have gotten along too well with William Carey.

The 1991 Persian Gulf War in Kuwait and Iraq gave some Southern Nazarene University students a chance to declare one thing that God seems to want to say to us through Jonah. When United Nations forces started their bombing campaign over Iraq, yellow and orange ribbons showed up everywhere, signaling people's solidarity with coalition military personnel. Trees on our campus and even a traffic sign or two sported yellow ribbons.

Then, one day, John and Jamie Zumwalt came to class wearing little green ribbons. That, they said, was to call attention to the spiritual lostness of those Muslim families affected by the war in Iraq and Kuwait. The green ribbons signified that they were praying for the lost Muslims of the Gulf region. Not many other students joined John and Jamie in wearing those green ribbons. Too many Jonahs around, it seemed. The Iraqis, after all, were the enemy. In 1991, praying that God would comfort and bless Iraqis seemed to some almost an act of treason.

Jonah missed the boat. And so have we!

Are the heathen lost? Yes, they are! Are we heartbroken over that? I'm not sure. We may be too much like Jonah.

To many believers, the 1,200 or so words of Jonah's story is a great children's tale that teaches us not to disobey God. Nothing more, nothing less. Reducing Jonah to merely an object lesson on obedience is a popular misuse of it. God went to great lengths to keep His plans for Nineveh from being thwarted by Jonah's disobedience. Jonah's story clearly shows that God doesn't lightly gloss over disobedience. Still, lessons about the dangers of disobeying God are simply footnotes to Jonah's main point. This has to be more than an obedience lesson, for although Jonah winds up obeying God, God is still very unhappy with him at the end of the story. Jonah's obedience or disobedience was never the main issue.

Some of Jesus' last words to His disciples are what we call the Great Commission.1 Matthew's version of it says: "Go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you" (Matt. 28:19-20).

People think of this command as the primary Scriptural motivation for missions. It certainly is a powerful one. Yet, Jonah's story clearly shows us that the Great Commission is not a brand-new thought. The Great Commission is simply a restatement of God's passion for "all nations" found throughout the Bible. Jonah's story is part of the biblical call for cross-cultural missionary outreach. Looking at Jonah, we see that our missions motivation does not grow out of one or two isolated divine commands in the New Testament. Any passion we have for missions is rooted in the very character of God.

Jonah did not want to reach the lost Ninevites. He wanted to restrict God's providence to the Israelites. He didn't want those Ninevites to have any part in Abraham's legacy. He was wrong. It was God, the very God those Ninevites had offended with their sin and idolatry, who wanted to reach out to them. God did not send us a Savior because we first begged Him to be merciful and save us. God has always taken the initiative. After Adam and Eve sinned in the Garden of Eden, they did not go looking for God. It was God who came seeking them. Robertson McQuilkin has written: "It is not too much to say that every major activity of God among men since the Fall has been a saving, missionary act." That's the God Jonah's story clearly reveals.

So, Yahweh is clearly a missionary God. He is a God who both seeks the lost and sends others to seek them. Part of God's message to Abraham in Genesis 12 is a promise that all peoples would be blessed through Abraham's descendants. That call is the basis of the Great Commission in Matthew 28:19-20 and of "you will be my witnesses . . . to the ends of the earth" (Acts 1:8). These words of Jesus are restatements of what God had been saying to His people from the time of Abraham. (More on Acts 1:8

Jonah declares that Jehovah is the Creator (Jonah 1:9). It's also clear from Jonah's story that God did not create the world and then sit back to watch it run. God got directly involved in Jonah's life. His story indicates that a direct connection that exists between God and natural events, a connection that a secular scientific worldview balks at seeing. In Jonah's story, God made the first move. He called Jonah to go to Nineveh. Then He continued to actively affect events. God caused the storm, and then it was He who stilled it (Jonah 1:4, 12). It was God who "prepared" the great fish (Jonah 1:17). Clearly, God does more than use events. He makes things happen.

Jonah's story shows us that God's dealings with us are in terms of building a relationship, not a cold appraisal. His will is not fixed and static. Instead, He continually interacts with us. God comes seeking, searching, and then sending. In life's changing situations, we never see God perplexed on what to do next. That seems clear from Jonah's story.

As a side note, God used the storm to draw the pagan sailors to Himself. Those sailors were impressed with God's hand in stilling the storm after dumping Jonah overboard. So, they "feared the Lord exceedingly, and offered a sacrifice to the Lord and took vows" (Jonah 1:16). It's hard to know their level of understanding. We can not assume that they had arrived at the same understanding of God as we have. Yet, after having been disappointed by a man who clearly knew what God was up to, these sailors are greatly impressed by Jonah's God. While the story's focus quickly returns to Jonah, these sailors' brief appearance reveals God's missionary character. This little episode reiterates God's desire to draw all nations to Himself.

Some Christians view religion as something exclusively cultural. "We have our religion; they have theirs," they say. They think the various religions have developed to fit different cultures. Such a feeling isn't something new born out of 21st-century pluralistic tolerance. Throughout Old Testament times, many Israelites felt that Yahweh especially belonged to Israel. The Holy Spirit is using Jonah's story to refute that belief.

The fish swallowed Jonah even as the grateful sailors sacrificed to Yahweh. What a dramatic picture! The pagan sailors who had not known Yahweh gratefully acknowledged their deliverance by Him. At that same time, Jonah, who had believed in God all along, sank below the waves, apparently going to his death.

Just before the sailors threw Jonah overboard, he told them they were dealing with the Creator of the universe and not a mere tribal deity. Earlier, however, such a limited tribal deity seems to have been in Jonah's mind. When he headed for that ship at Joppa, Jonah was running -- or at least he thought he was -- away from God's presence. Jonah was apparently thinking that no god (Yahweh included) had much power outside the country that worshiped him or her (or it). As Jonah would soon be reminded, however, God has cosmic sovereignty. His reign was not limited to the Temple area in Jerusalem or even to the borders of the Promised Land. He is far more than a tribal god.

The people on that Tarshish-bound ship believed in many tribal gods. When the shipmaster awoke Jonah, he begged him: "Call on your God" (Jonah 1:6). The captain was not trying to figure out if there was one true God or many. He just wanted to be sure every possible deity was being called on.

Sadly, Jonah failed to tell that ship captain that the Israelites' God was not a limited tribal deity. The truth began to come out a bit when Jonah admitted to the sailors that he was running from God (Jonah 1:10). Then, as we've mentioned, in his prayer from inside the fish, Jonah says that what many people worship are actually false deities (Jonah 2:8).

God's purpose in sending Jonah to Nineveh was redemptive from the outset. Why else would He send a prophet there? Jonah didn't need to be in Nineveh to predict its downfall. That message could have been given in his hometown. Other prophets had already given such long-distance predictions concerning heathen nations and cities. Had the Lord permitted Jonah to speak about Nineveh from Palestine, Jonah probably would not have rebelled as he did. Hearing that he had to go to Nineveh awakened Jonah's rebellious spirit. As he intimated, Jonah sensed that a warning of God's judgment would open the door to the Ninevites' repentance. He hated those Ninevites. So he refused to go (Jonah 4:2).

One of the Jewish special holidays is called Yom Kippur. Each year, during Yom Kippur celebrations, the book of Jonah is read aloud in Jewish synagogues. Despite hearing Jonah's story over and over again, the Jews have missed the boat with Jonah. Jonah's story heaps should make us dismissive of nationalistic exclusivism. No nation has a corner on God. The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob yearns for "all nations" to honor Him. Therefore, we do not hold up Christ as the one and only mediator between God and human beings out of a sense of religious superiority. We proclaim, "There is no other name" because it is so. If Jesus was God Incarnate come to earth, then He and He alone can save us. That's why God has to be so missionary in His character. There is no other way of salvation.

The cartoon character Dennis the Menace was talking one day to Joey as they walked away from a neighbor's house. As the neighbor lady -- Mrs. Wilson -- watches them walk away, both boys munch on a cookie.

Dennis turns to his friend and says: "Mrs. Wilson gives you a cookie not because you're good but because she's good."

Don't the words that the cartoonist put into the mouth of Dennis the Menace make good theology? Little Dennis' evaluation of Mrs. Wilson illustrates how God deals with us. God doesn't bless us because we're good. He does so because He's good. That's a lesson from Jonah's story.

Jonah knew that "salvation comes from the Lord" (Jonah 2:9). It is grace -- God's grace -- that saves us. Our Protestant heritage makes a big deal of the fact that we are saved by faith, not good works. By the grace of this missionary God, salvation is offered to us.

"It's not fair for God to damn people who've never heard!" a college student said to me one day. God doesn't act unfairly. The truth is that judgment has already been passed on all the human race. Our individualistic age misses the implications of the solidarity or unity of the human race. We draw back from joining Isaiah in crying out that we are part of "a people of unclean lips" (Isaiah 6:5). We Westerners heavily emphasize individualism while overlooking collective responsibility.

A sports analogy may be helpful here. A basketball team may have a superstar player who always outscores everybody else. Even at that, his team may lose lots of games. As highly motivated and talented as that gifted player is, he or she will never share a championship moment because he or she is on a losing team. We, too, are members of a losing team. No matter how good an individual on that team may be, it is still a losing team. For that person to be a winner he or she will have to get on a different team.

God is trying to find ways to draw us (and everyone else) into His saving grace. Don't Peter's words that God "is not willing that any should perish" (2 Peter 3:9) remind you of what Jonah's story showed years before. Then, Jonah's story ends on a clear note of God's concern for His whole creation. There is that haunting final question from God: "Aren't people worth more than cattle?"

Think about Jonah's story. God Himself was the one most concerned about Nineveh. No one on earth was pleading for Nineveh to be spared, certainly not Jonah. The Assyrians were his country's bitterest enemies. As it dawned on Jonah what was happening, it galled him to think that these cruel Assyrians could be objects of Jehovah's care.

As we try to explain our relationship with God, we sometimes use friendship terminology. Yet, that relationship is different from a human friendship. For instance, we may be friends with another human being even though we don't share very many of the same interests. Our relationship with God is far different. We cannot approach Him on a simple "live-and-let-live" basis like we can with human friends. Rather, we must be so absorbed with Him that we say with Paul, "It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me" (Galatians 2:20). Therefore, if God is the missionary God that Jonah's story reveals, then no one should claim a close relationship with Him if he or she is not also intensely missionary. Missions is not simply one of God's many concerns. It is His central concern. It should come as no surprise that Christ's Church has been the most spiritually alive when it has been its most missionary.

Through the centuries, there have been those heavily burdened for lost peoples. In the 1500s John Knox prayed: "Give me Scotland or I die." In the wake of his prayer, revival and reformation swept across that country. Knox's great prayer for an entire country has inspired others through the years. One missions organization, DAWN (Discipling A Whole Nation), uses John Knox's prayer to call for others who will burden themselves for the evangelization of entire countries.1 In light of what Jonah's story reveals to us about God, it's clear that Knox was not any more burdened for Scotland than was God Himself! No one is more intensely missionary than God Himself.

My wife, Barbara, and I spent 10 years as missionaries in Italy. On several occasions, people there mentioned to us Christianity's long history in that country. Then, they would ask us: "So, why have you come?"

Good question. While there aren't many Protestant churches in Italy, we saw Roman Catholic church buildings everywhere. I once visited Calatafimi, a little village on the island of Sicily. That Italian village has less than 5,000 people. Yet, it has 17 Roman Catholic churches (and one little Nazarene one). The number of Catholic churches there was far above average for an Italian village of that size. Still, I understand why people wondered what we Nazarene missionaries were doing in a country with such a long Christian heritage.

Barbara and I offered ourselves for missionary service because we felt God's call to cross-cultural ministry. We went to Italy because the Church of the Nazarene asked us to begin the fulfillment of our missionary call there. Behind all of that, however, was the missionary character of God Himself. Because most Italians were baptized as babies in Roman Catholic Churches, they call themselves Christian. Sadly, active participation in any church ranges from a low of 10% of Northern Italy's population to a high of 30% in the South. Even those Italians who were faithful in religious rituals have rarely found inner peace or true shalom. God yearns to reconcile those Italians to Himself. We believe that's why God opened the doors for us to give ten years of our lives to witnessing, preaching, and teaching in Italy.

Jonah understood some things about God's character. Sadly, however, his heart was out of tune with the Lord's. The things that broke the Lord's heart did not break Jonah's. Not only was Jonah out of tune with God. At times, he wasn't even playing the same song as God. What about us? Are our hearts in tune with the Lord's? Do the things that break His heart also break ours? If not, we're no more than a band of Jonahs!

John Wesley was one whose heart ached to resonate with the Lord's, but he struggled with getting that to happen. First, he tried living a holy life in his own strength. At Oxford University, Wesley, together with his brother and some friends, was so diligent in his devotional and spiritual life that other students at the university made fun of him by nicknaming him and his friends the "Holy Club." In spite of what Wesley was doing religiously, he still felt a void inside. Hoping to remedy that, he went to America as a missionary to the Indians. Being a missionary seemed to him like the ultimate sacrifice. He wasn't exactly like Jonah in the sense that he was running from God's call. Still, Wesley did not have his heart in tune with his Creator.

As Wesley crossed the Atlantic Ocean, his ship ran into a storm. That little wooden ship was tossed around so much that Wesley feared for his life. Among the passengers was a group of lay Christians. They were Moravians, part of a lay organization that sent out some of the first Protestant missionaries. This group on that ship with Wesley was also on its way to evangelize the New World. During that storm, these Moravians faced death with a quiet fearlessness. Wesley was both impressed and humiliated. Those Moravians had a deep, calm assurance, which he had not found despite diligently following religious rituals.

Eventually, the ship landed safely at Savannah, Georgia. There, while Wesley tried to evangelize the Indians, he also probed for the source of the Moravians' inner peace. One day, Moravian leader Spangenberg asked Wesley: "Do you know Jesus Christ is your Savior?"

Stunned at the man's audacity, Wesley, who was a Church of England priest and former Oxford University professor, stammered out: "I know he is the Savior of the world."

Spangenberg countered: "True, but do you know that He has saved you?"

After brushing off the question, Wesley spent an unfruitful three years evangelizing the Indians. When he returned to London, he began attending a Moravian Bible study. One night, while listening to someone reading aloud in the group from Martin Luther's introduction to Romans, Wesley felt his heart "strangely warmed." It was the witness of the Spirit he had longed for. Up to that point, John Wesley had expended a great deal of energy trying to do what God wanted. But Wesley's disciplined spiritual exercises had not brought him inner peace. Outward conformity is not what God wants. He wants our hearts to beat in tune with His. In that Bible study meeting in London, Wesley finally came to know God intimately. When that happened, he too became intensely evangelistic and missionary. (John Wesley's influence today)

Jonah didn't want to go to Nineveh. He was not at all in tune with the missionary heart of God. The spiritual hardness of his heart did soften temporarily when he was inside the fish. Jonah didn't have the missionary heart of God, who has reached out and is reaching out. It isn't Jonah's disobedience that made him such a tragic figure. Rather, it's the callous way in which he finally obeys.

Unfortunately, the spirit of Jonah is alive today, permeating the ranks of God's people. I've heard local church leaders grumble that spending a nickel or dime of each church dollar on world evangelism saps too much of the local church's financial resources. Such "me first and foremost" thinking sounds far more like Jonah than God. Others complain about sending resources to evangelize the whole world while there are still many unsaved people in the U.S. Doesn't that sound like Jonah? It's certainly not something from the heart of God.

God's compassionate mercy toward Nineveh does not mean He blindly tolerates sinful behavior. Before they repented, the Ninevites faced a sentence of destruction. It is clear, therefore, that great cities, like great men, can fall under God's judgment. Still, God yearns to deal mercifully and kindly with us. This amazing story reveals a divine tenderness that reaches out to both Nineveh and Jonah. God's heart is a missionary heart. If we were in His place, we probably wouldn't put up with either Jonah or Nineveh.

"Can a good God send anyone to hell?" some ask. No. Indeed, He's trying not to. God freely offers salvation to the likes of both Jonah and Nineveh. He has a magnanimous missionary heart. He doesn't "send" anyone to hell. It's a choice each individual makes for himself/herself.

As our hearts get in tune with God's heart, we will find ourselves becoming ever more missionary. Great prayer warriors have always been intensely missionary. As I think about the godly people I've known, almost all carry a heavy burden for world evangelism. On the campus of Southern Nazarene University, the group that promoted prayer the most was called World Christian Fellowship.

On the other hand, spiritual shallowness dims our sensitivity. We'll not sense God's missionary heart. A spiritual shallowness makes far too many Christians think of God like a celestial Santa Claus. Like Jonah, they miss the boat. God is not a Santa Claus; He is a missionary! He doesn't come offering gifts. He comes offering Himself. If we take Him, we must become intensely missionary, reaching out to the unreached Ninevehs of our day.

The biblical story of Jonah is an fascinating narrative of divine calling and human reluctance. Jonah was told by God to go preach repentance to the people of Nineveh. He found himself grappling with fear and prejudice toward that foreign society. His initial refusal to heed God's command led to his infamous flight in the opposite direction on a ship. It was a clear case of resistance to the unfamiliar and the unknown. Yet, through a tumultuous trip involving a great fish and eventual obedience, Jonah reluctantly fulfilled his mission.

The story illustrates the themes of God's universal concern for all peoples and the transformative power of obedience. It challenges Jonah's ethnocentric worldview and invites us to reflect on our attitudes toward those we think of as foreigners or "those other people."

Ultimately, Jonah's experience is a powerful reminder of the importance of humility, compassion, and openness in cross-cultural mission efforts.

The Book of Jonah is often called "the missionary book of the Old Testament" because it uniquely emphasizes themes of God's mercy, repentance, and the inclusion of non-Israelite nations in God's plan. Here are two reasons why the story of Jonah earns this title: