TL;DR:

Jesus modeled incarnational ministry by living among the people He served, speaking their language, and sharing their daily lives. Cross-cultural missionaries today are called to do likewise—learning local languages and customs, empathizing with those they serve, and becoming bicultural without abandoning their own identity. This process of identification builds trust and makes the Gospel credible.

Question: What is the most challenging part of being on the mission field? Answer: It may be that of becoming truly bi-cuoltural, of being so "at home" in another culture that you are no longer feel like an "outsider.".

In the opening words of his gospel, the Apostle John declared that God Himself had lived "among us." The Message paraphrase of the Bible colorfully renders John 1:14 as "The Word became flesh and blood and moved into the neighborhood," while theo Common English Bible says, "He made his home among us." The classic Amplified Bible says that Christ "tabernacled (fixed His tent) among us."

These various expressions all point to the fact that Jesus lived as a First-Century Jew. He spoke the mother tongue of the people. He ate at their tables and celebrated holidays with them. He traveled around with them. He interacted with their children. Jesus was truly at home in First-Century Jewish culture.

In this day of instant communication, airplane travel, and Google Translate, rookie missionaries can be tempted to try shortcuts or even opt to bypass the hard work of language learning and cultural acquisition. That might seem like a strategic move that will allow them to launch into ministry immediately. However, omitting language and cultural acquisition would be a short-sighted decision for new missionaries. Good missionaries never see following Jesus' example of "moving into the neighborhood" as a waste of time. Like Jesus, perceptive missionaries spend time acquiring fluency in the language of a people group. They adapt to unfamiliar customs. They embrace a culture not their own and come to feel at home in it. There are no painless shortcuts on that road.

Remember what Jesus said in Matthew 18:2-4 about becoming "like little children"? To be sure, Jesus used those words in a different line of thinking than that of going as a cross-cultural missionary. Nonetheless, that idea of becoming like a little child does speak to the subject of assimilating the culture of the people to whom we want to minister. We do need to become like little children as we enter an unfamiliar culture. We must go in with our eyes wide open, trying to learn everything we can. Sure, it will take time, and all missionaries will make mistakes along the way, but the process will increase their long-term productivity as Christ's ambassadors.

If we're going to minister in the way Jesus did, we must "pitch our tent among them" (as some scholars say the Greek verb in John 1:14 could be rendered). Will "living among them" be hard and sometimes seem sacrificial? Yes, but we must do it if we are going to follow the example of our Lord.

This blog on Christlike attitudes and actions that need to be present in cross-cultural missionary service is one of a dozen articles in the "Missionary ministry that reflects Christ" series published in Engage magazine.

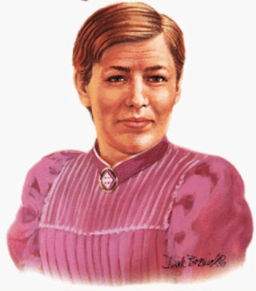

What can we learn from the woman whose biography by Carol Christian was titled God and One Redhead?

Mary Mitchell Slessor (1848 - 1915) was a Scottish Presbyterian missionary who served in Africa. In 1876, she went to what is now Nigeria and died there after 40 years of Christian missionary work. In addition to preaching the gospel, she was a school supervisor, dispenser of medical aid, mediator of village disputes, promoter of women's rights, and a rescuer of children from infanticide. She embraced a standard of living at the level of the people she served.

"More African than the Africans"

Missionary work that follows First Century patterns involves settling in with a people group for a good spell. It means living with them and connecting with them on a variety of levels. It involves eating their food, learning their language, and enjoying their humor. It includes becoming able to genuinely empathize with them.

Such purposeful participation by missionaries in another culture is called "identification." It does not necessitate "going native" and totally forsaking one's own culture. It means becoming bicultural in addition to becoming bilingual.

Over the centuries, many Christian missionaries have exemplified good identification. One example is Mary Slessor who served for 40 years in Africa.

Born into a poor Scottish family in the middle of the 1800s, red-headed Mary felt a call to ministry at age 11. Coincidentally, that same year, she went to work in a textile factory. Her alcoholic father could not provide for his family, so young Mary worked ten-hour days, six days a week, to help support her family.

Missionary David Livingstone, who was then in Africa, became Slessor's hero. At his death, she determined to follow in his footsteps. And she did. Two years later, at age 29, Mary Slessor arrived in Calabar, a region of what is now Nigeria.

Mary was initially assigned to work in a city school with other European missionaries. Her heart, however, was in doing pioneer work among unreached people. Other missionaries spoke of the "savagery" and "heathenness" of such people, but that was exactly where Mary felt the gospel needed to be lived and proclaimed.

Four years later, she was able to move out into a tribal area. Deciding to live with the local people as they lived, she moved into a traditional African house. As she settled in, identifying with the people she had come to serve became a core value. Among other things, she discarded the multi-layered petticoats worn by many European missionary ladies, choosing instead simple cotton dresses more in line with what African women were wearing.

Because of Mary's strong personality, other missionaries sometimes found it difficult to relate to her. Not so with the Africans. Her identification with them was so authentic that an African church leader once said she was "more African than the Africans."

Indeed, because of Mary Slessor's close identification with the people, her living out the gospel among them helped her to be instrumental in settling tribal hostilities. She successfully battled witch doctors' "healing" practices and fought other practices contrary to God's design. For example, she got one tribe to give up their practice of killing infant twins. She was so respected and influential that she came to be called "the white queen of Calabar."

In authentic identification, missionaries can say (either out loud or at least to themselves), "When I am among you, I feel at home." That seems to be where Mary Slessor arrived in her pursuit of identification.

-- Howard Culbertson, hculbert@snu.edu

"Mary Slessor's desire to make a difference was not deterred by her gender or the status of women in those days but was fueled by a sincere determination to be a blessing for the people of Africa." -- Aneel Mall, Northwest Nazarene University graduate student

S – Surrendered her life to God's call, venturing into the unknown.

L – Loved the African people with compassion and devotion.

E – Endured hardship, disease, and danger with unwavering faith.

S – Spoke boldly against injustice and cultural oppression.

S – Shared the gospel tirelessly, bringing light to remote villages.

O – Overcame fear and prejudice through Christlike humility.

R – Rescued abandoned children, offering them hope and dignity.

More biographical sketches in the "Doing missions well" series published in Engage magazine.

Like acrostics? Here are more of them

In the context of cross-cultural Christian missionary work, "identification" typically refers to the process by which missionaries immerse themselves in the culture, language, and customs of the people they are serving. This involves not only learning about the cultural idiosyncrasies but also adopting certain aspects of the local way of life. The objective is to relate to and connect with people in the ethnolinguistic people group to which they are ministering.

Identification is a key to fruitful cross-cultural missionary ministry. That's because it builds trust, understanding, and acceptance within the local community. By demonstrating respect and love for the culture and customs of the people we are trying to reach and serve, we can build meaningful relationships with people in that culture. That opens the door for us to better communicate the Gospel message.

This identification approach contrasts with a more top-down missionary model, where missionaries may seek to impose their own cultural norms and practices on the people they are trying to reach. Identification in global missionary ministry requires humility, empathy, and cultural sensitivity.

The way Bible translators have rendered the wording of John 1:14 include:

Even in the age of digital media, would-be missionaries should see two important lessons in the wording of John 1:14.

"Picking up your whole life, moving to another country, entering and immersing yourself in another culture, and working day in and day out to bring the Gospel to the people is a pure reflection of God’s heart and character." -- Madi Haskell, Nazarene Bible College studnet