More classic art masterpieces used as illustrations

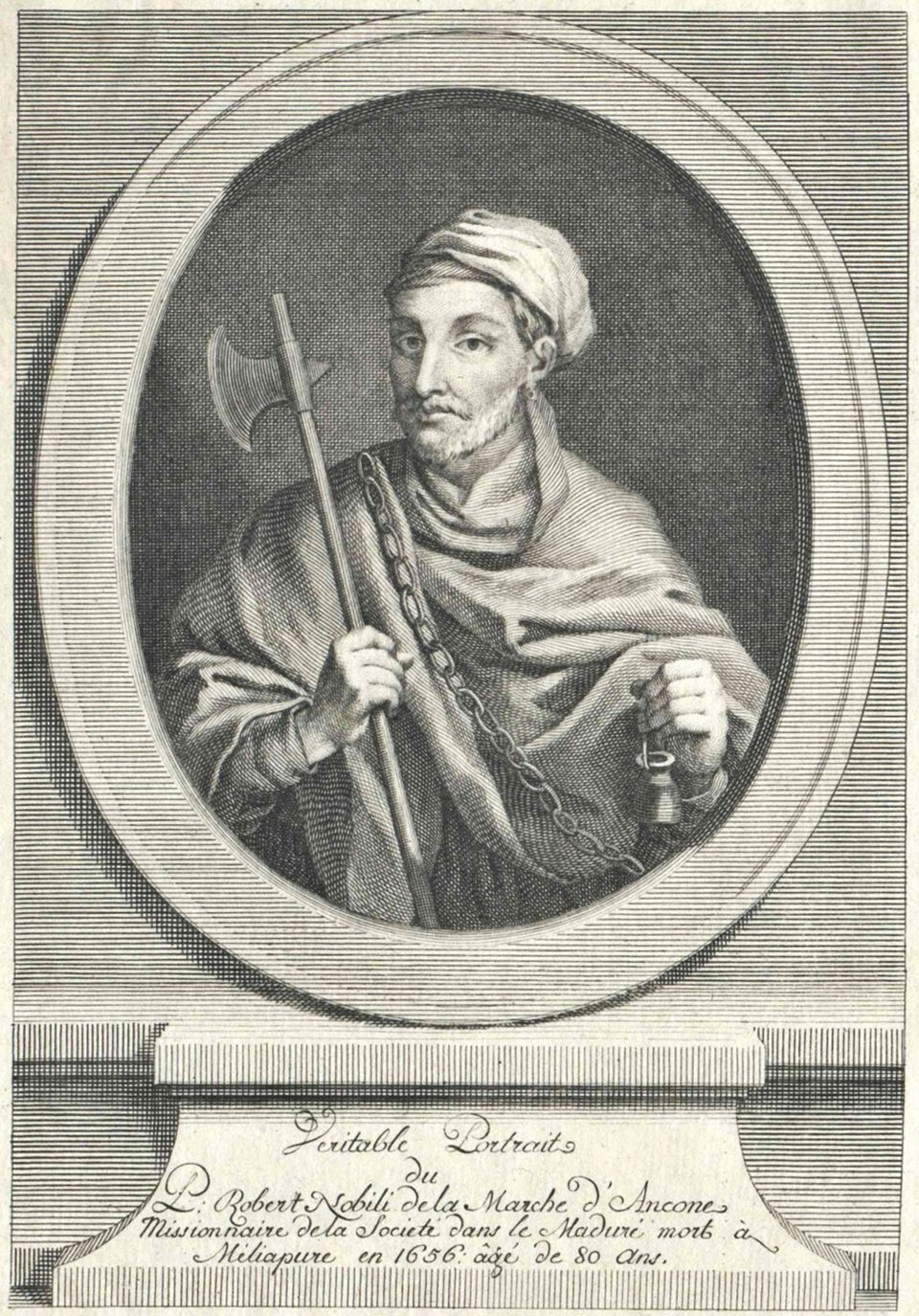

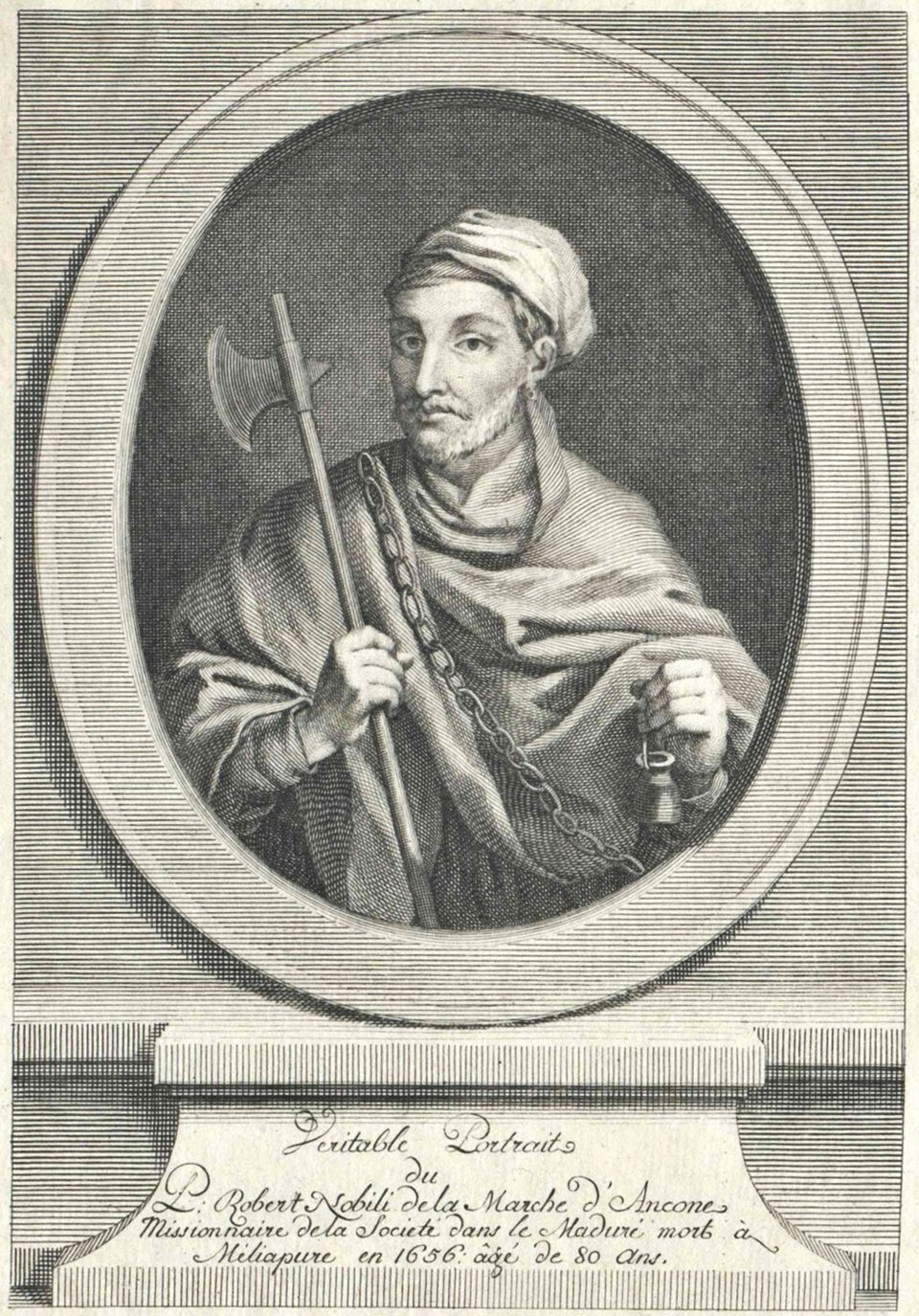

Roberto de Nobili was born in Rome in 1577. He was the first son of an Italian nobleman who was a general in the papal army.

When Roberto announced his intention to enter the Jesuit order and become a missionary to Asia at the age of seventeen -- a year after his father's death -- the family strongly objected. Their opposition was not to the idea per se of his entering the priesthood. The de Nobili family had contributed numerous clerics to the Church, including several Cardinals and at least two Popes.

Roberto's folly, his family said, was in choosing the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits). That path, they argued, offered few possibilities for ecclesiastical advancement and position. However, Roberto was adamant: "When God calls, no human consideration should stop us." So, in 1596, ignoring his family's wishes, he entered the Jesuit novitiate with the goal of becoming a foreign missionary.

Initially, de Nobili appeared destined for Japan. Then, in response to appeals for reinforcements in India, he volunteered for missionary work in the Portuguese colony of South India. After a period of orientation and language study and the usual delays, de Nobili sailed for India in April of 1604. More than a year later, in May of 1605, he arrived in Goa, a Portuguese island off the southwest Indian coast.

Adjustment to new living conditions was not easy, and during his first months in India, Roberto became quite ill. Then, early in 1606, he was sent to the Fishery Coast to minister among the Paravas, a large people group of outcastes.

While most Paravas lived along the coast where they were fishermen and pearl divers, some of them had migrated inland. By and large, the Paravas of the Fishery Coast professed to be Christian, but it was common knowledge that in the 1530s, several thousand had been baptized in exchange for Portuguese protection from the Muslim raiders from the north. Roberto observed that the Paravas, like other converts he had met in Goa and Cochin, dressed like Portuguese, used Portuguese names, and, for the most part, conducted themselves like Portuguese.

In his first seven months with the Paravas, Roberto immersed himself in studying their culture and the Tamil language.2 Possibly, Roberto de Nobili would have spent his entire missionary career working with these people and, therefore, would have remained on the outer fringes of India's life. However, his superior Alberto Laerzio asked him to move to Madurai, a city that was a five-day trip inland.

A mission had been established there in 1594 by a fifty-four-year-old Portuguese Jesuit, Gonçalo Fernandez. Though not necessarily by choice, Father Gonç also worked exclusively with Paravas, who had immigrated to Madurai, and with Portuguese tradespeople. The hub of his activity was a missionary compound on the city's outskirts. Fernandez said mass in the small mission chapel, heard confessions, directed the school for boys, and oversaw the mission dispensary. He had attempted to reach higher-caste people with the gospel and sought to interest the Nayak (the regional king) in Christianity. However, these evangelistic efforts among people of caste were unsuccessful. In eleven years, the Madurai mission had seen no converts from Hinduism. All of the one hundred individuals to whom Father Gonç also ministered were either Paravas or Portuguese.

Roberto struggled to understand why the Madurai mission was confined to the outcaste Paravas and Portuguese immigrants. He felt himself fortunate, therefore, to have become associated with the Hindu schoolmaster that Fernandez had placed in charge of the school. From the schoolmaster, Roberto was astounded to learn that the term used by the Indians to refer to the Portuguese and their converts, Parangis, was not -- as the missionaries believed -- a Tamil word meaning simply "Portuguese." Rather, it signified polluted, uncultured, contemptuous foreigners and their proselytes. Parangis were despised, the Hindu schoolmaster said, because they ate meat, drank wine (usually to excess), bathed irregularly, wore leather shoes, and ignored the rules of social interaction.

Because of this, when the missionaries proudly referred to themselves and their converts as "Parangi Christians," they were unwittingly erecting a huge barrier between themselves and the Hindus.

With his Hindu mentor's help, Roberto came to see how the caste system was the cornerstone of Indian society and culture. To violate caste was to threaten "divinely-ordained structures of life." To the Hindus, the single most important thing about people was their caste.3

When the Portuguese first came to India, the question was asked: To which caste do these foreigners belong? It seemed to the Hindus that the Portuguese were ignorant, uncouth, unscrupulous people who were unworthy to associate with anybody except the outcastes. How else could one explain their disregard for basic religious and social principles? No Indian who valued his rank in society or who treasured his religious faith would ever consider adopting the ways of these foreigners. This was the reason, according to the schoolmaster, why Hindus avoided contact with the Portuguese except for trading purposes. To be touched by or even looked upon by a Parangi was contaminating.

Roberto became convinced that Hindus would never listen to the gospel until a break was made with Parangi Christianity. He, therefore, determined to disassociate himself from people and customs which might identify him as a Parangi.

So, he sought the support of his older colleague. He shared his ideas with Father Gonçalo, attempting to persuade him of their soundness. Fernandez, however, had been in India since 1560, and for nearly twelve years, he had worked virtually alone to establish a Christian base in Madurai. As vicar of that parish, he was responsible for all the believers in the area. So what he heard from Roberto filled him with dismay.

Roberto told him he wanted to deny that he was a Parangi. He wanted to speak only Tamil and avoid touching or even associating with the Portuguese and the outcaste Christians. He wanted to bathe daily, sit down cross-legged, and refer to himself as a sannyasi (a Sanskrit word meaning "one who has given up everything," but for a Brahman, being a sannyasi was the last stage of life). He wanted to eat no meat and wear wooden clogs and a saffron robe instead of the traditional Jesuit black cassock.

Such a course of action, responded Father Gonç also, would be a repudiation of three generations of missionary work in India and an irretrievable concession to social evils that Christianity should eradicate. Hundreds of missionaries had given their lives in India in an attempt to plant the Church and root out social evils. For Roberto and him now to withdraw from outcaste believers and follow the prohibitions of caste would be turning their backs on the Indians who had first accepted the gospel. Additionally, the other changes Roberto was suggesting, such as refusing to eat meat or wear leather sandals, wearing Indian clothing, speaking only in Tamil, and calling himself a sannyasi would deny his priestly identity and seemingly sanction harmful superstitions and prejudices.

Roberto decided that he had no alternative but to appeal to his superior, Laerzio, who confessed that he was uneasy with the unconventionality of Roberto's ideas. Was it necessary, he asked, to go to such extremes? Laerzio affirmed that he longed for the conversion of Hindus as much as any missionary in India. Still, he could not himself grant permission for such radical departures from the traditional missionary strategy. Nonetheless, Laerzio indicated that he would consult with the Archbishop.

After several weeks, a response came from the archbishop. According to Laerzio, the archbishop said Roberto could cease using the name Parangi and refer to himself as a sannyasi. No mention was made, however, of Roberto's other proposals.

Meanwhile, the relationship between de Nobili and Fernandez deteriorated further. "How was it possible," Father Gonçalo asked, "for a new missionary who has been in the country less than three years to determine the best way to evangelize India?"

Roberto was not to be deterred. He ignored Father Gonçalo's protests. As long as he had the approval of Laerzio and of the Archbishop, Roberto felt he could continue.

In his letters, Roberto described the growing breach between himself and his older missionary colleague. It was evident, Roberto said, that there was no possibility of reconciling two missionary philosophies. So, he decided to move ahead and accept the restrictions of caste and refuse to condemn any social custom or idea, even the despised Hindu practice of suttee4. He moved from the missionary compound into a hut in the Brahman quarter of the city and shaved his head except for a small tuft of hair. He spoke only Tamil hired a Brahman cook and houseboy and became a vegetarian. Like all Brahmans, Roberto limited himself to one meal a day. He abandoned the Jesuits' black cassock and leather sandals for a saffron robe and wooden clogs. To cover the "nakedness" of his forehead, he put sandalwood paste on his brow to indicate that he was a guru or teacher. He referred to himself not as a priest but as a sannyasi. Eventually, he ate only with Brahmans, and for a brief period, he also wore the Brahman thread of three strands of cotton cord draped from the shoulder to the waist as a sign of rank. He bathed daily and cleansed himself ceremonially before saying mass.

Roberto's first Hindu convert was the Sudra schoolmaster. By the end of 1608, just two years after arriving in Madurai, de Nobili had baptized at least ten young men of caste. As his circle of disciples expanded, he became friends with a Brahman Sanskrit scholar named Sivadarma, who, after considerable hesitation, permitted de Nobili to see and study the Vedas and the Upanishads. Because of that, Roberto de Nobili is thought to be the first European to study Sanskrit and even to see the Hindu sacred writings. At the beginning of their relationship, Sivadarma may have believed that he was converting the personable European to Hinduism, but by 1609, Roberto had persuaded Sivadarma to read the Bible — which de Nobili referred to as the "Christian Veda" — and to accept Christian baptism.

Acrostic: Meaning of Baptism

With that baptism, Roberto faced two difficult questions. He knew that, as a Brahman, Sivadarna would be reluctant to worship with people of lower castes. Would it then be proper to segregate the believers according to caste? Secondly, was it necessary, as other missionaries insisted, for Sivadarma to discard the triple thread and shave the kudumi or the single braid of hair marking him as a member of the highest caste? Roberto resolved the first problem by forming a totally Brahman church. For an answer to the question of the thread and the kudumi, he appealed to his superior Laerzio, insisting that the thread and the kudumi braid were social symbols rather than religious ones.

Father Gonçalo did not hide his mounting distress. The young missionary's innovations, including acceptance of the caste system, seemed detrimental to the spirit of the gospel. Fernandez warned that Roberto's innovations would derail the existing work in Madurai. They might even jeopardize Christian work across India. Fernandez made a trip to the coast to talk to priests there. Then, he wrote a denunciation of Roberto's activity and sent it to the Archbishop. Soon, the entire Jesuit mission in South India was debating the wisdom of de Nobili's approach. Many of Roberto's friends and even members of his family in Rome were dismayed when they heard of the extent to which he was adapting himself to Indian customs. To try to calm the storm, Laerzio wrote a letter to the Jesuit General defending de Nobili.

By the end of 1609, Roberto had gathered around him some sixty new converts, including a few Brahmans. The new converts were not asked to violate the rules of caste or to give up any custom which was not indisputably idolatrous. The signs of caste, such as the thread and the kudumi, were given a Christian blessing.

Two years elapsed before de Nobili's methods were officially condemned by a member of the church hierarchy in India. That censure was issued by Nicolau Pimenta, newly appointed Papal Visitor5 to the provinces of Goa and Malabar. Pimenta declared that Roberto's accommodations went too far.

Pimenta's condemnation represented a serious obstacle to the continuation of de Nobili's strategy. Both Pimenta and Roberto wrote detailed reports to the Jesuit General. Communications between Rome and Goa were painfully slow, and so another two years passed before a reply came. In the meantime, nearly twenty of Roberto's disciples had lapsed back into Hinduism, and his supportive superior, Laerzio, had been replaced by Pero Francisco.

The response from the top Jesuit leader arrived in August of 1613. It indicated that de Nobili erred on three counts:

"You must," the Jesuit General wrote, "during the day and in the sight of all, deal freely with the Fathers of the other residence, go to their house and talk with them, and they, in their turn, must be allowed to come to your house without any restriction and not by night only." Francisco's added comments included a prohibition against de Nobili's baptizing any further converts unless and until he submitted to the conditions stipulated by the Jesuit General.

Roberto responded that these changes would undo all he had accomplished and would sound the death knell of his mission to the Hindus. He refused to make changes based on a single sentence in the Jesuit leader's letter, i.e., "No change should be made which would compromise the existence of the mission."

The affair dragged on for another five years, during which time Roberto could not baptize anyone. In 1617, Pope Paul V ordered a conference to be held in Goa in which de Nobili would defend his missionary methodology. At that meeting, twenty theologians and priests were present, including two Papal Inquisitors. They were charged with deciding the future of Roberto's innovative mission strategy. The debate was intense. Then came the vote. . .

Seven-step case study reflection guide

1The last name of an Italian would normally be "di Nobili."

2Tamil is a Dravidian language spoken in Southern India and in Northern Sri Lanka (Ceylon). De Nobili could not study Tamil from written material designed to teach it, for none existed at the time. He learned the language from the Paravas, whose limited vocabulary provided at least an introduction. Proficiency in Tamil was difficult to acquire. It bore no resemblance to the major European languages. Its alphabet consisted of thirty letters plus a few symbols borrowed from Sanskrit. Twelve of the letters were vowels called "souls," and the other eighteen were consonants referred to as "bodies." Seventeen of the "bodies" could be combined with the twelve "souls," making a total of 204 characters. These, together with the thirty original letters, made a total of 234 different signs that Roberto had to master — all of them in script.

3Indian society was composed of four principal castes: the Brahman (sacerdotal or

learned), the Ksatriyas or Rajas (governors or warriors), the Vaisyas (traders or farmers), and the

Sudras (serfs). Each major caste category was divided into subcastes. Finally, there were

the despised outcastes. The Hindu schoolmaster was, like the majority of caste people, a Sudra.

4Suttee was the self-immolation of Hindu widows on the

funeral pyres of their deceased husbands. It was supposedly evidence of the widows' devotion.

Roberto said he had seen 400 widows die in this fashion in Madurai.

5A person commissioned by the Pope to make official inspections and

report back to him.

This case study in its original form is in Alan Neely's Christian Mission: A Case Study Approach, published by Orbis Books. Adapted and used under the educational "Fair Use" provision of U.S. copyright acts.

-- Howard Culbertson, hculbert@snu.edu

Jesuit missionary Roberto de Nobili was a pioneering figure in the history of Christian missions in India. Nobili is remembered for adopting local Indian customs and practices, particularly those associated with the Brahmin caste. He faced criticism and opposition from some within the Church who viewed his methods as compromising doctrinal integrity. However, Nobili's strategy did bear some fruit. He attracted a number of converts from the Brahmin caste and established a Christian community that retained many aspects of its Indian cultural heritage.

Roberto de Nobili's approach to cross-cultural missionary work continues to be studied and debated within the context of intercultural and interreligious dialogue. It speaks to questions about the boundaries between contextualization and syncretism in cross-cultural evangelism and discipleship.