TL;DR: Humans acquire culture through two related but distinct processes. Enculturation is the lifelong, mostly subconscious process of learning one’s own culture. It shapes personal identity and equips people to function within their society. Acculturation, by contrast, occurs when people enter a new culture and consciously adapt to it, learning to function effectively without losing their original identity.

"So much of what happens culturally is below the surface, and the below-the-surface stuff is what influences all of the above-the-surface stuff. If we truly want to understand the culture, we must dig deeper than the superficial." -- Scott Fox, pastor and Nazarene Bible College student

Adapted with minor editing from Cultural Anthropology: A Christian Perspective. Used under the educational "fair use" provision of U.S. copyright acts.

It was snowing and bitterly cold as the man pulled out of his driveway onto the snow-covered street. His mind was on his job as he thought about the meeting that would begin his working day. Suddenly the rear end of his car began to slide to the left on the hard-packed snow. With this, the rear end began to slide to the right. Immediately he turned the steering wheel to the right. The car's rear end continued to slide from left to right with the man steering in the direction of the slide until he had the car under control. Once he had the car under control, he drove on to work at a slower pace, concentrating on his driving. When he arrived at his workplace, he recounted the harrowing experience to fellow employees, saying, "Wow. That happened so suddenly I didn't have time to think. I just reacted instinctively."

Instinct is a word we commonly use to describe certain types of behavior in animals and humans. As with many terms, instinct carries shades of meaning that vary depending on whether it is used in a popular sense or in a scientific one. In the scientific sense, all behavior can be classified as either reflexive, instinctive, or learned. As to scientific usage, C. T. Morgan and R.A. King, authors of an introductory psychology book, note that behavioral scientists define instinct as a pattern of behavior that is inherited instead of learned.

When it comes to human beings, with the possible exception of a few behaviors that mature without practice, we cannot say with certainty that there are any instinctive behavior patterns [in humans]. Human beings seem to have become so sophisticated in learning to adapt to their world and in teaching their young how to adapt that instinctive behavior is not considered to be a prominent human characteristic.

They go on to explain that in order to qualify as instinctive behavior, three conditions must be fulfilled:

The animal relies on instinct, or "innate fixed action pattern" (Rogers 1965:22). For example, we once had a black walnut tree in our backyard. I had gathered some nuts, planning to process them. Then I discovered they had already begun to rot. So, I dumped them in the backyard. My attention was caught sometime later by a squirrel. Because the ground was frozen, he was frantically trying to hide those nuts wherever he could -- on the log pile, under the storage shed, in a hollow place in the snow, even on a windowsill.

Such a pattern, as exhibited by the squirrel, is more complex than a muscular reflex since it involves more than muscles. On the other hand, it is not as flexible as purposive behavior since the motor elements run off in a rigid mechanical order. It is not the same as a chain reflex because it is not motivated in the same way.

Animals appear to have a sign stimulus releaser. For the robin, it is the red breast. For the moth and wasp, it is a particular odor. For the mother hen, it is a distress call. In humans, however, a reaction is made to any of a large array of stimuli, and the reaction is appropriate to some object or situation of which all these stimuli are signs. The reaction is governed by the situation such as a "child in distress," rather than by any particular stimulus.

Most behavioral scientists would say that human beings have few instincts and others would say they have none. Without instinct to direct behavior, how does a person function? Well, human beings have to learn their behavior. Anthropologists call this learning process enculturation.

Noam Chomsky suggested that human beings may have innate language ability. That is, they have something that provides language readiness. By way of example, he noted the following things:

That's why it is possible for the Christian to say the following:

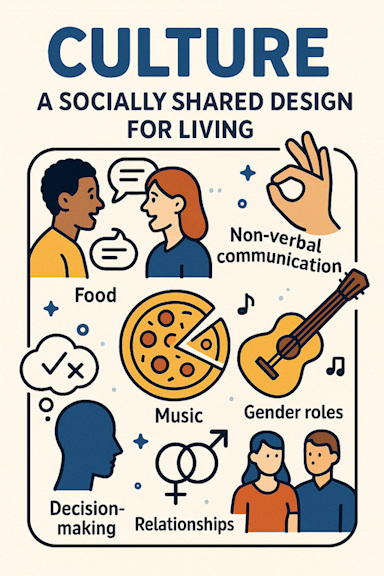

Sociologist Talcott Parsons spoke of the birth of new generations of children as a "recurrent barbarian invasion." He said that was because human infants do not possess culture at birth. They have no conception of the world, no language, and no morality. It is in this sense that Parsons uses the word "barbarian" in reference to infants. They are uncultured, unsocialized persons. All an infant needs to live and cope within the cultural context awaiting him is acquired through the process termed enculturation by the anthropologist and socialization by the sociologist. We may define enculturation as the process by which individuals acquire the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that allow them to become functioning members of their societies.

Awaiting the infant is a society possessing a culture, an ordered way of life. The child possesses certain possibilities for processing information and developing desires making it possible for that ordered way of life to influence him. These long-lasting competencies, standards of judgment, attitudes, and motives form the personality. The personality, in turn, influences the culture.

Enculturation, says E. Adamson Hoebel, is "both a conscious and an unconscious conditioning process whereby man, as child and adult, achieves competence in his culture, internalizes his culture, and becomes thoroughly enculturated." One internalizes the dreams and expectations, the rules and requirements not just for the larger society seen as a whole but also for every specific demand within the whole. Society does whatever is necessary to aid any one of its members in learning proper and appropriate behavior for any given social setting and in meeting the demands of any challenge. Enculturation begins before birth and continues until death. Thus, one learns respect for the symbols of the nation through reciting a pledge of allegiance and singing the national anthem in school. A person learns with whom he may be physically violent (a wrestling competitor) and with whom he cannot (the little child down the street). A person becomes aware of his rights, obligations, and privileges as well as the rights of others.

Some saints and revolutionaries successfully internalize the norms of their society and then make a novel system out of them. Sometimes totally new novel systems displace established ones. For instance, Jesus Christ introduced a way of new life and the new proceeded to supplant the old. The American Revolution, which took place on a continent where Europeans were in the process of settling, permitted a novel system to progress through time without undue hindrance from the Old World. There is no question, however, in the minds of students of history and comparative sociology that the new, in each of these cases, was clearly an outgrowth of the old.

The enculturative process results in identity: the identity of the person within the group. Society seeks to make each member a fully responsible individual within the whole. While the enculturation process may occasionally alienate some persons, society's intent is responsible participation.

God called attention to this when He gave the Hebrews the Ten Commandments. He said in effect, "Don't let the system of family, economy, interpersonal relations, and religion be abused. Let each one work and do his part for the good of the group and each member of the group. In this way, I will be honored." It is no wonder that Jesus and Paul, living in New Testament times, sought to uphold the ideal of one's responsibility within the corporate or group setting. "Render to Caesar" and "obey the government, for God is the one who has put it there" are very specific commands or instructions building upon previously laid foundations.

The enculturation process has two major aspects: (1) the informal, which some call "child training" and in some senses precedes and in other senses runs concurrently with (2) the formal, more commonly termed "education." The former is most likely to be carried out within the context of the family and among friends. The latter is carried out in institutions of learning, sacred or secular.

As we have stated, the infant enters a culture already formed. Some psychologists suggest that the stresses and strains within the womb begin forming the child's personality. From the moment of birth, however, there is no question as to the socio-personality influences upon the child. The process of increasing awareness, called by some "canalization," is effected in four major stages: (1) the emerging awareness of the "universe" about him; (2) the differentiation of his universe from that of others; (3) the stabilization of his notions about his universe; and (4) the increase of control over his universe (Bock 1969).

Jean Piaget spent a lot of time observing and running experiments with children. He then assigned time periods to a series of stages, as the following summarizes:

These age periods are not absolutes but provide a guide to the maturation of the child. Piaget does feel, however, that the child will go through these stages in order, although the rate of movement will vary from child to child. The child does not cast off the attainments of earlier periods. Rather, the child retains earlier forms of intelligence integrating them with more advanced forms.

Societies differ in the care of the young (Bock 1969:56). One means of classification is based on whether child care is done by an individual, by a group, or by both. North American parents tend to give individual attention to their child, with the mother primarily responsible for the child's care. However, when both parents work, the American child is likely to be placed in a childcare center to be cared for by a small team of professionals. One of the trademarks of Israeli kibbutzim is that the children are cared for by paraprofessionals, none of whom is necessarily a parent of the child.

Another means of classification is whether child care is by a relative, a non-relative or both. In most societies, the child is cared for by the natural parents or a close relative, such as an elder sibling or grandparent if the parent is unable to care for him. However, in cultures or subcultures where wealth or prominence dominates, the child is cared for by a nonrelative such as a tutor, nurse, or maid. The Egyptian princess in the Bible who discovered baby Moses in the river sent Moses' sister Miriam to find a wet nurse and maid. Miriam brought Moses' natural mother. The princess did not expect the girl to secure the natural mother, for anyone could and would have served insofar as she was concerned.

A third means of classification looks at whether child care is done by parents, another relative or both. In Maya-related societies of Central America, as well as in Samoa, the eldest child in the family is given the primary responsibility for the care of the younger children. In Latin societies, this is likely to be the eldest girl. The responsibilities for the baby may start even before the child is weaned. Such care continues until the age of ten to twelve. At that time, the father begins to pay more attention to the preparation of the boy for adulthood, and the mother brings the girl into the complex workings of the home.

Child care may also be classified by mother or father or both. There are several obvious biological reasons for assigning care of the child to the female parent. Among the Black Caribs of Central America, this is accentuated by the practice of couvade. The mother carries on her normal life after the birth of the child, and the father symbolically goes to bed. Among the Maya, the mother cares for the child until he is weaned, as long as two-and-a-half years after birth; and then other members of the family participate, especially the child's grandmother.

In habituation, human beings learn those aspects of culture not regarded by the culture as specifically learnable techniques. Babies, being helpless, have their needs fulfilled for them. The way the need is fulfilled is almost as important as the fulfillment itself.

By the time a child is able to fulfill some of his own requirements for food and sleep, his habits are well established. These habits may be changed several times during the course of maturation, but even the need to change and the capacity to change are developed into habits. In one sense, the habits are the culture. When the habits of the people change, the culture changes.

Each individual in a given society is provided the means of individual improvement. No society is without an education program, though few have as extensive and comprehensive a one as that found in Western nations. The formal education provided in Western nations through a graded school system is provided in other societies through social, religious, political, or economic mechanisms.

The Pocomchi of Central America have a socio-religious organization called the cofradia. It provides all members of the society between the ages of twenty and forty with a formal education in keeping with the needs and demands of society. Each member approaching the age of twenty is elected into one of the eight cofradia in the community and serves for a period of two years. After this period of time, he rests at least a year before accepting another election into a cofradia for a new two-year term of service.

When participating in the activities of the cofradia, he does everything the senior members do. In this way, he is trained in all the social processes known and used within his community. By the age of forty, he is fully qualified to handle any problem the society faces and to maintain the operation of the community productively alongside the other leaders.

In every society, each member has someone for whom concern can be shown. This person might be part of his nuclear family, his extended family, an age or interest group, or a political or economic team. In societies organized around kinship, this other person is likely a nuclear or extended family member. In societies that have economic trading teams, as among some Australian Aborigine groups, a close caring relationship develops between trading partners. In societies where there are age-level organizations, as in certain areas of Africa, members of such organizations grow into a deep and abiding relationship with others of the same age level.

In matrilineal societies where the lineage and inheritance are traced through the mother's line rather than the father's, the biological father is a relatively insignificant member of the family team. He is replaced by a sociological father, the mother's brother in most instances. The child's maternal uncle therefore functions in the male caring role and is responsible for the child's well-being and increasingly mature behavior. In societies in which a joking relationship permits two members of the society to tease and criticize one another, a closeness develops which is impossible within a society where these roles are almost completely separated.

In most societies where the informal and formal practices of education involve the master-apprentice relationship, a different type of preparation develops than that stemming from the classroom lecture system. The master teacher is not simply training his pupil or apprentice to do the task in question. He is also teaching him to be a good master. Proper master behavior is passed on to the apprentice with the skill.

Knowledge is primary in North American society, where there is a teacher-pupil relationship rather than a master-apprentice one. A student will likely use the content learned sitting under a lecturer but may not gain communication skills.

In Mayan societies, which practice the master-apprentice relationship, outsiders have established schools based on teacher-student. When students returned to their villages after studying at the Bible institute, they presented the same lectures to their own people because the apprentice models the master. Even the illustrative material, given by a lecturer with an urban and industrial background, was used verbatim even though little of it was relevant to the rural and farm people in the audience.

In societies where formal education is based on the teacher-pupil educational relationship, telling is the primary means of teaching, i.e., lecture. Association between teacher and student is minimal, primarily within the context of the classroom. This being so, the teacher's influence on the student is only in the specific area of the course content. The rest of the teacher's experience and insight is lost to the student. The student who gets any closer to the teacher than that usually reports, "He's human after all." Change through the generations is by chance or the accumulation of influence of many teachers in many classrooms. Evaluation is thus of minimal value within the life of the student because only "end results" are tested and evaluated, i.e., the examination. The process by which one achieves learning is never questioned or evaluated. It is assumed that if one can handle the final exam well, the process of learning has been adequate.

In societies where formal education is based on the master-apprentice relationship, modeling good behavior is primary. The proper behavior of the skill or trade is communicated as well as the proper behavior of the master to his apprentice. There tends to be maximum involvement between the two since they spend a great deal of time together. There is great opportunity for directed change with maximum impact on the life of the pupil by the master. Evaluation is in terms of the whole. The skill is only a relatively small part.

Jesus related to His disciples through a master-apprentice relationship. By the time He went to be with His Father, the bulk of the disciples were ready to carry on the work He had begun, and they assumed positions in the early church in keeping with their preparation. In John 17 Jesus prays for His apprentices, linking them with God. "They were yours; you gave them to me . . . As you sent me into the world, I have sent them into the world" (John 17:6, 18). Earlier He had referred to them as branches of a vine, Himself being the vine. He speaks of the ones they will be contacting and bringing into the kingdom as "grapes."

Every human who fulfills his biological destiny passes through four major stages or "crises" in the life cycle: birth; puberty, or maturity; marriage, or reproduction; and death. Every culture acknowledges these major periods in some way, though some are made more prominent than others. Some cultures handle these experiences calmly and quietly; others exhibit much anxiety. In the latter case, the cultural emphasis is on the crisis situation. Within each society, therefore, these rituals or rites of passage allow a member to properly move from one condition of life to the next.

Pre-birth rituals, such as baby showers prepare society for the new infant's arrival. The newborn is "baptized" within eleven days in the Philippines and somewhat later in other Catholic- and Protestant-influenced cultures. The shower and baptism are the rituals, the means, of transition from the unborn state to the born state. Some societies take this crisis so seriously that they require the husband to go to bed as a replacement for the woman so that no harm will befall her and she will be able to provide sustenance for the baby. The Caribs, the Ainu people, and the Chinese of Marco Polo's time all practiced couvade.

It has only been within the last two hundred years that human beings have had a full scientific explanation for the biological and genetic process of conception. Some cultural groups of people do not connect the act of physical, sexual intercourse with the resultant pregnancy. Australian aborigines believe that a child is the reincarnation of an ancestral spirit. This belief seems to negate any relationship between the sex act and conception, though there is the belief that a woman's body must be opened in some way to permit the entrance of the ancestral spirits.

Failure to connect conception and the act of intercourse is considered by some as naiveté or ignorance. There is an increasing awareness, however, that it may simply be the cultural suppression of physical reality. In such cases, the cultural form is designed to support the social system. For example, ancestor worship and totemism are important themes in the lives of many Australians. The continuity of the totemic group is sustained by the doctrine of spiritual reincarnation. A tight focus on physical paternity would undermine the sacred institution.

The matrilineal Trobrianders believe the male plays no role in conception. To them, the spirit of a dead clan ancestor enters the womb when the woman is wading in the lagoon. It grows and becomes a child. The neighboring Dobu believe semen is coagulated coconut milk which causes the menstrual blood to coagulate and form a fetus. Many peoples of the world note the cessation of the menstrual flow as a sign of pregnancy. Others take note of breast changes, loss of appetite, "morning sickness," or a tendency to laziness on the part of the woman as signs of pregnancy.

Numerous anxieties attend the birth process. These include: (1) the child will not develop ideally, (2) the fetus will miscarry, (3) the birth will be difficult, or (4) some evil spirit will adversely affect the fetus and later the newborn child. Therefore, special attention is given to those who attend the birth (fathers may or may not be present) and to those who see the child after birth (to the Latin, strangers may cgive illness and death by means of the evil eye). What adorns the baby after birth is also important (the Pocomchi tie a string around the wrist of the newborn to protect the child against the evil eye).

Whereas nominally Christian societies use baptism and christening as indications of the social acceptance of the child, other societies make use of special presentations and naming ceremonies. Among the Ashanti, a child is not considered a human being until eight days after birth. At that time, the child is ceremonially named and publicly presented. Should it die before eight days have passed, it would be disposed of; for the Ashanti would believe that it was merely the husk of a ghost child whose mother left it to go on a trip and then returned to claim it. Among the Swazi -- distant neighbors of the Ashanti -- for the first three months of life, a baby is only a thing. It is not named, and the men cannot hold it. If a baby under three months of age dies, it cannot be ceremonially mourned.

Thus, the question of when life begins is handled differently among various people groups. Catholic-based cultures hold that life begins at conception. Protestant subcultures differ in when they believe life begins. These beliefs range from conception to as late as birth. The medical profession in the United States has accepted a position implying that life begins sometime between the third and fifth months. Therefore, many medical professionals will support abortions up to this time. The Ashanti and Swazi and numerous other societies of the world say human life should not be numbered from birth but perhaps from a point as late as three months later.

There are large variations in the quality and quantity of creative productions between cultures and even within the same culture at different times. Indeed certain characteristics of a culture may give birth to or at least make possible greater creative production.

The first of these characteristics would be a level of technology and economy that would generate sufficient material wealth to make possible the time and opportunity for creative activity. Persons living in a society where every person is involved full-time in subsistence activity are less likely to engage in creative activity.

The second characteristic of a creative society is the presence of a communication system that allows for the maximum exchange of ideas and information. Societies that restrict communication also restrict the exchange of ideas and information on which creativity feeds.

The third characteristic is a societal value system that socially and economically rewards creative acts. The fourth characteristic is related to the third. Societies with a climate of acceptance will experience higher levels of creativity than societies that punish creativity economically, socially, or criminally.

The fifth characteristic is opportunities for privacy. Privacy is often necessary for creative production. Although some societies provide or allow for sanctuaries, other societies have no real concept of privacy. In addition to privacy, the sixth characteristic is the existence within the social system of social mechanisms that permit or spark the formation of disciples or peer groups, such as art colonies, professional associations, and other forms of social organization that stimulate creativity.

The last characteristic is an educational system that encourages free inquiry and rewards individual research and creativity. Societies with educational systems geared to transmitting what has already been discovered and traditional knowledge are less likely to produce creativity than those whose educational system encourages questioning and challenging traditional knowledge and exploring new frontiers of knowledge.

Whereas enculturation is learning the appropriate behavior of one's own culture, acculturation is learning the appropriate behavior of one's host culture. In effect, one enters a new culture as a child and is enculturated into the new society through the process of adaptation to that society. To the degree that people do not permit the structures and relationships of their former society to unnecessarily restrict their adaptation, they can become acculturated into the new. Good acculturation allows them to maintain their principles, and thus their self-respect, and yet cope with all the challenges and opportunities of the new culture.

However, they may never become fully accepted as a member of the new culture for a variety of reasons. Anthropologist William Reyburn finally realized that he was known as an outsider simply because of the way he bent over to "haunch" with the Indian men to whom he ministered. But his fluency in the language and his lifestyle permitted his acceptance into the new society with a minimum of strain.

It is wise at this point to distinguish between what is known as culture shock, the negative emotional response to the mismatching of cues from the new culture with cues from the old, and culture stress, the realization that one will never fully assimilate within the new and develop the ability to cope with the various demands of the new. Most people entering a new culture or subculture experience culture shock to some degree. Having passed through it, they imagine that they will have no further problems in that area. However, there is likely to be ongoing tension because of the awareness of cultural differences. It leaves no emotional disability, but one simply has a sense of incompleteness within the context of the new.

Acculturation and assimilation differ in the degree of adaptation to the new. In acculturation, people adapt to the degree of their effectiveness within the new context. They assume they will leave again and return to the society of their birth. They are fully accepted and respected members of the new society yet, in reality, they have a dual identity.

Assimilation is the more extreme process. It comes from the realization that one will never return to the society of origin. So one takes on the entire way of life of the new. The process is more thorough, comprehensive, and likely lengthier. First-generation immigrants may achieve a high degree of adaptation. Second-generation people most likely reach a high degree of assimilation. (Note: Some anthropologists do not distinguish between acculturation and assimilation. They speak of this difference in intensity of response in other ways.)

Once people become aware of the principles underlying the acculturative response, they will increasingly realize that all encounters can be labeled as cross-cultural. That is because no person has the identical sociocultural background as another. Even twins always wheeled together in a tandem walker wind up with different experiences. For instance, one may look more at the street and the other more at the yards of homes being passed. This subtle difference will produce separate cultural backgrounds, even though slight.

Marriage brings together representatives of two separate subcultures. Schools bring together people from different local neighborhoods. Churches are made up of people with a variety of religious experiences. Differences brought to awareness by socialor geographical mobility cause few problems within the corporate body as long as an agreement is made to ignore them. They can become very serious, even to the point of disruption, if they are made issues. For example, a musical background to the morning prayer in a church service is no problem until someone whose background did not incorporate this practice challenges it as distracting.

As the foundation for enculturation is positive reinforcement, the foundation for the acculturative process is the functional equivalent. Direct equivalent focuses on the form of expression and produces the response. It looks the same, therefore it must be the same. Functional equivalent, on the other hand, focuses on meaning or significance and produces the response. It may not look the same, but it does the same thing -- what is intended. Thus, a functional equivalent is something that performs the same function as a different thing. The two things are equivalent in meaning rather than form.

Marvin Mayers says that a key principle in adapting to another culture is the question of trust, "Is what I am doing, thinking, or saying building or undermining trust?" The question of rights, privileges, and status considerations must follow from such a question in the cross-cultural context even though they might be primary within the context of one's own culture. If trust is not built within the context of interpersonal and intergroup relationships in the cross-cultural encounter, there will always be a challenge to rights, privileges, and status considerations. This will produce tension and alienation that will adversely affect all that is done individually and corporately.

Every society has a way of protecting each "inborn" and "adoptive" member from the risk of losing absolutes and self-respect. This device is the cultural cue and is the society's provision for correct behavior and behavior response. In fact, it is the cue that the child learns through the enculturative process.

The sum total of all cues learned is the culture itself. The outsider simply needs to tune into the correct cue for his purpose and do whatever he has to do. A teetotaler in a drinking community simply needs to learn the cue for "I don't drink, but you may." Then he can maintain his own self-respect, allow the other to maintain his self-respect, and still leave the channels of communication open for further contact and mutual influence.

In the early days of television, many Christians refused to have one in the house. But they slowly adapted to the new subculture. They found they could control their viewing and make use of the television as they had the radio, which their parents had initially reacted to adversely. Years ago, Future Shock by Alvin Toffler alerted people to many ways we are challenged to adapt. One way we realize the adaptive process is going on is because we are able to handle today what we assumed yesterday was too much for us.

The blockage to adaptation and assimilation comes from an attitude termed ethnocentrism. In its positive expression, ethnocentrism allows one to be satisfied and complete as a person within the context of his own culture. In its negative effect, ethnocentrism subtly communicates the superiority of one's own over all others. The end result of ethnocentrism is the reinforcement of one's own lifestyle, the inability or unwillingness to change, and the subtle demand that others change to become like oneself to be fully accepted. More on ethnocentrism

Such a closed attitude to change -- which is taking place all around us -- results in a phenomenon termed "drift." Society changes in inconsistent ways rather than consistent ones. It changes by whim rather than by design. Its members must take what comes rather than being able to plan for that which will aid them.

That which is cautiously guarded against by adherence to form and expression rather than meaning and by concern for the reinforcement of one's own culture to the exclusion of the other usually has the opposite effect from that which was intended. Instead of reinforcement of the good desired within one's own context, evil forces are let loose. Instead of respect comes the loss of respect. Instead of reinforcement of principle, there is abandonment. Instead of growth, there is immaturity. Instead of truth, there is falsehood.

The end of adaptation and assimilation is bilingualism and biculturalism. Bilingualism refers to one's fluency within the cross-cultural context. One is able to speak two or more languages fluently and is known as an adequate, correct speaker of both. Biculturalism refers to one's ability to cope with all the demands of verbal and nonverbal behavior so well that he is accepted as a member of a culture rather than an outsider.

After all, what is our mission in life: to make our culture known, to make our hang-ups the hang-ups of others, to force others to change their lifestyles, and to create great gaps in communication? Or is it to introduce men and women to the Lord Jesus Christ and allow Him through His Spirit to do His work in their lives as He wills?

-- Howard Culbertson, hculbert@snu.edu

Enculturation and acculturation are processes through which individuals acquire cultural knowledge and behaviors. However, they occur in different contexts and involve different dynamics:

Enculturation:

Acculturation:

Strategies for Coping with Culture Shock